From an ancient Chinese recipe to industrial production in Europe

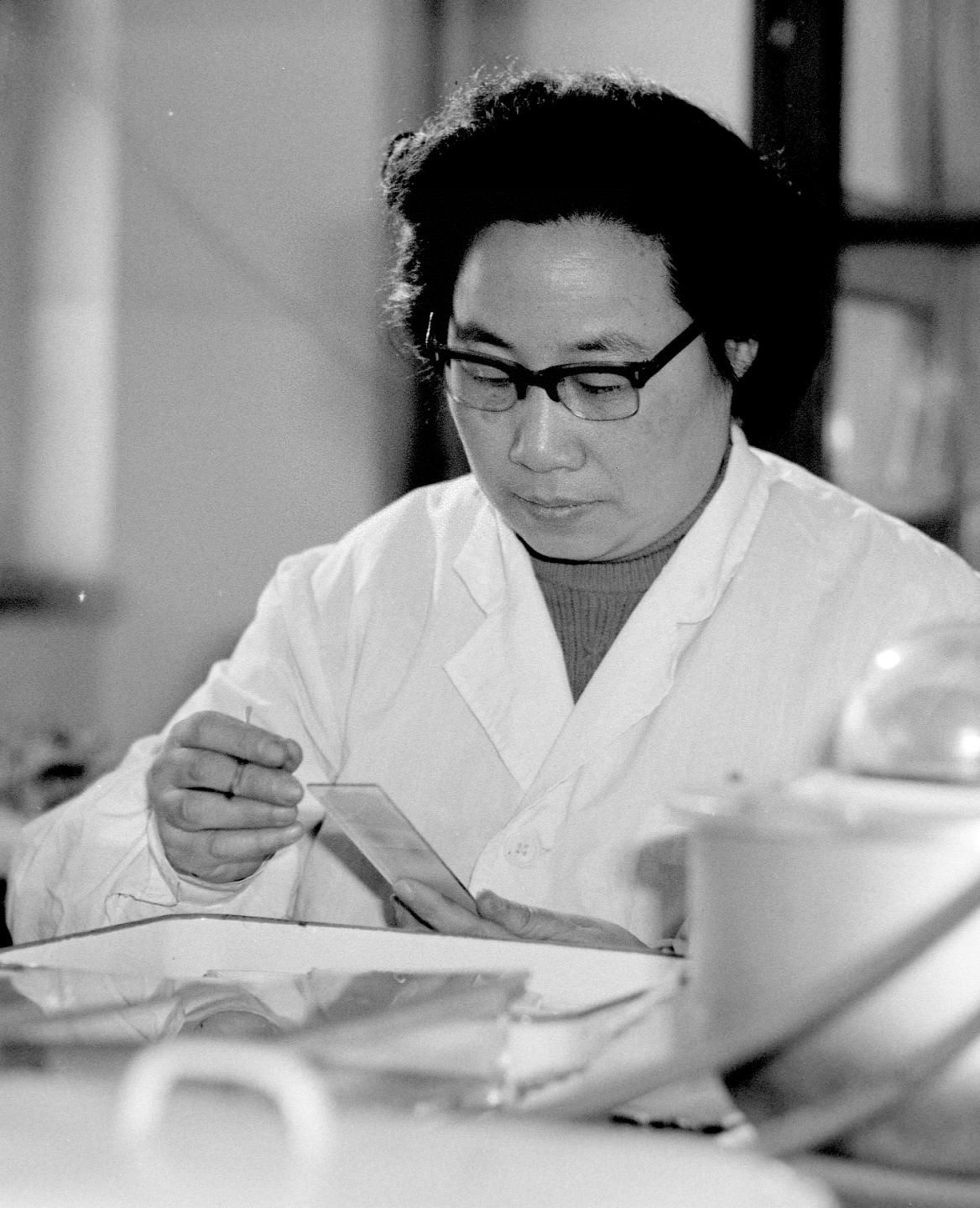

On 5th October, a Chinese pharmacologist was awarded the Nobel Prize in Natural Sciences for the first time: Professor Tu Youyou was recognised for her immense contribution towards reducing instances of malaria worldwide. Volker Müller, Business Manager at the European Chamber, pays tribute to Professor Tu’s remarkable career.

A few years ago when I was preparing to go to Namibia as a volunteer on a conservation project, my major health concern was, of course, malaria. Internet research revealed several preventative drugs, but all of them had potentially severe side-effects and were very expensive. Besides this, certain parasites had become partly resistant to them, so their use was not recommended for long stays in high-risk areas. When asking for advice at the Beijing Healthcare Centre for International Travellers, I heard about Artemisinin[1] for the first time, a cheap, herb-based drug that can be used for treatment after the onset of malaria symptoms, which has little side-effects, making it ideal for self-medication if no medical assistance is available.

A Nobel (sur)prize

On 5th October this year, it was a big surprise for the Chinese academic community when Professor Tu Youyou, a pharmacologist at the Chinese Academy of Chinese Medical Science in Beijing, was awarded half of this year’s Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine “for her discoveries concerning a novel therapy against malaria”.[2] The award made her the first Chinese Nobel Prize Laureate in Natural Sciences.

Professor Tu’s career was somewhat non-academic compared to most individuals involved in mainstream science. She never gained a post-graduate degree and never took part in any international exchange programmes. Described as a modest person, Professor Tu’s work was characterised by field studies in malaria-infested tropical villages and research on a shoe-string, rather than by an academic environment of perfectly equipped laboratories.

Before China’s reform era, personal fame of researchers wasn’t exactly encouraged, and the Chinese academic system (as in most other countries) has difficulties acknowledging, let alone celebrating, an unconventional career path. In all likelihood it is a combination of these factors that prevented her from being awarded a top science award in China and being admitted to the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The Nobel Prize Committee, however, based their decision solely on the outcome of her research and her contribution to human health.

A profound discovery

Malaria is one of the most dangerous infectious diseases in the world. In 2013, the World Health Organization (WHO) recorded 198 million new cases, leading to the death of 584,000 people. Ninety per cent of all malaria-related fatalities occur in Africa, mainly in children less than five years of age, who account for 78 per cent of the deaths.[3]

In the 1960s, mosquitoes developed resistance to Chloroquine—the only available anti-malaria drug at that time—and the mortality from malaria increased dramatically, and China certainly wasn’t immune to the problem. Up until the late 1970s, large parts of Southern China, including Guangdong Province, were plagued by widespread malaria. In 1967 Professor Tu became part of a large national project to find new ways of treating the disease.

By this point, scientists worldwide had screened 240,000 chemical substances without success. Professor Tu and her team turned to traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) to continue the search. Although TCM did not have treatment for malaria per se, it did have various treatments for different kinds of intermittent fever, which provided valuable clues as to which herbs might be useful. Eventually, the leaves of sweet wormwood (Artemesia annua), described in an ancient recipe from 340 AD,[4] were identified as being the most effective for treating the symptoms of malaria. Professor Tu continued her research applying methods of modern pharmacology, testing Artemisinin first in animals and then in human clinical trials, which she was the first to volunteer for.

Food for thought

Premier Li Keqiang was effusive in his praise of Professor Tu, stating that the Nobel Prize “showcases China’s growing strengths and rising international standing.”[5] And of course, the Nobel Prize award was celebrated on Chinese social media. However, while Professor Tu’s contribution to worldwide healthcare—especially in developing countries—is indisputable, awarding a scientist whose career and approach are both somewhat out of mainstream science provides some food for thought.

Today, China spends around 5.5 per cent of its GDP on healthcare, in central Europe this figure exceeds 10 per cent, yet there is still a lack of resources in healthcare, so it is crucial that money is allocated in the most efficient way. Much like China in the 1960s, in today’s developing countries many people only have access to traditional medicine, due to economic reasons. For example, in Ghana self-treatment of malaria with herbs costs 1/16 of hospital treatment.[6] Meanwhile, pharmaceutical companies have to spend billions of euros to develop new drugs. Perhaps this Nobel Prize award can motivate both health authorities and medical companies to reconsider the balance between traditional and modern medicine. Almost all countries and nationalities have their own traditional medicines, and it is likely that there is still a great deal of potential to be released.

From discovery to production

Production of Artemisinin in commercial quantities through natural methods is limited by the volatile nature of sweet wormwood—it takes up to 10 months to cultivate, and its yield is affected by the weather, region and growing practices—and so far, synthetic production has not been possible. As an alternative approach, PATH, a global non-profit organisation, raised funds to develop a method for turning a living organism into Artemisinin. In 2013, French-based pharmaceutical manufacturer Sanofi announced the launch of large-scale production of semi-synthetic Artemisinin as an anti-malaria treatment.[7]

The positive impact that Professor’s Tu’s work has had in the fight against malaria is clearly stated in the scientific background of the discovery, provided on the Nobel Prize website:

“Artemisinin-based Combination Therapy has profoundly reduced the incidence of malaria, saving millions of lives worldwide.”[8]

“Artemisinin-based therapy has contributed to the significant reduction in mortality, particularly for children with severe malaria (>30%). The overall global death toll from malaria during the last 15 years has declined by 50% (WHO, 2015).”[9]

From ancient TCM that led to the outstanding research work of Professor Tu Youyou and finally to commercial manufacture by a European company – it has been a long but successful journey on the way to ensuring a stable supply of one of the most important drugs in the fight against malaria.

The 2015 Nobel Lectures in Physiology or Medicine will be held on 7th December and is webcast live at www.nobelprize.org. Videos of the lectures will also be available on the webpage a few days later.

[1] Chinese: 青蒿素, pinyin: qinghaosu.

[2] The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2015, nobelprize.org, Nobel Media AB 2014, 5th November, 2015, viewed 2nd November, 2015, <http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/2015/>

[3] Scientific Background Avermectin and Artemisinin – Revolutionary Therapies against Parasitic Diseases, The Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Insitutet, viewed on 2nd November 2015, <http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/2015/advanced-medicineprize2015.pdf> p.5

[4] The Handbook of Prescriptions for Emergency Treatments, written in AD 340 by Ge Hong

[5] Chinese premier congratulates Tu Youyou on winning Nobel Prize for medicine, Peking University, 6th October, 2015, viewed 2nd November, 2015, <http://english.pku.edu.cn/news_events/news/media/3966.htm>

[6] Traditional and Complementary Medicine Policy, chapter 5.2, Why people use traditional and complementary medicine, World Health Organization (WHO): viewed 2nd November, 2015, <http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s19582en/s19582en.pdf>

[7] Sanofi and PATH announce the Launch of Large-scale Production of Semisynthetic Artemisinin against Malaria, Sanofi, 11th April, 2013, viewed 2nd November, 2015, <http://en.sanofi.com/Images/32474_20130411_ARTEMISININE_en.pdf>

[8] Scientific Background Avermectin and Artemisinin – Revolutionary Therapies against Parasitic Diseases, The Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Insitutet, viewed on 2nd November 2015,

< http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/2015/advanced-medicineprize2015.pdf> , p.1

[9] Ibid, p.6

Recent Comments