Although the express logistics industry in China is going through a period of change and rapid growth, it has not been easy for foreign players to operate due to restrictive government regulations. However, the regulations are loosening, creating new opportunities for growth, and there are some reasonable investment opportunities for foreign companies, provided they take the necessary precautions. Michel Brekelmans and Stephen Sunderland of L.E.K. Consulting have provided the following report, which should give businesses looking to invest in this sector a sense of optimism.

China’s express logistics industry has enjoyed exciting growth of 20 – 30 per cent per annum in recent years. As China’s logistics market liberalises and consolidates, investment opportunities are arising for new investors, particularly those who can help China’s emerging titans develop better technological platforms, enhance service quality and expand their geographic reach.

Trade buyers remain keen to expand their businesses through inorganic growth – a trend that is also expected to pull in private, third-party investment or expertise as Government-sector lending plays a smaller role.

Explosive growth and local participants achieving scale

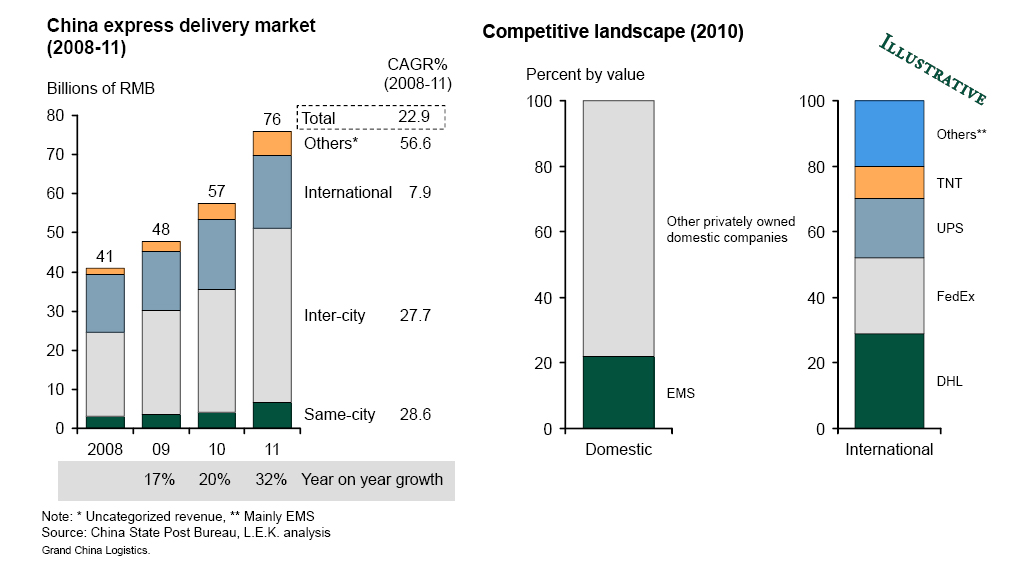

The growth experienced by China’s logistics industry has been underpinned by rapidly rising domestic demand for goods, and government policies supporting better and more efficient logistics services. With annual revenues valued at around RMB 80 billion in 2011, the express logistics market has seen compound annual growth of around 23 per cent between 2008 and 2011. However, the express logistics industry in China is characterised by two broad segments (domestic and international), which have very different competitive dynamics.

Figure 1: China express delivery landscape

The domestic segment has been experiencing substantially-faster growth than the international segment (28 per cent p.a. vs. eight per cent p.a. respectively), and whereas the international delivery segment is dominated by four global express logistics service giants, the domestic segment is served almost entirely by local players. Historically, a key driver of this dynamic has been the form of PRC Government regulation, which, for example:

- Permitted foreign enterprises to deliver only from companies within China but not from individuals

- Required foreign enterprises to either obtain a license to operate in China, or form joint ventures with Chinese entities, in order to gain more access to operate in the market

Although regulatory restrictions and local protection have been easing, foreign players’ higher-cost services have been unable to compete effectively in the domestic delivery segment.

Local firms have rushed in to service rapidly developing needs and a few domestic players have come to prominence on the national stage. Domestic companies are building scale and starting to extend feelers on an international basis. For example:

- EMS, the largest domestic express company and a state-owned enterprise, now has a fleet of around 10 aircraft and 10,000 land vehicles and has entered the international express delivery market

- SF-Express, the number-two player in the domestic express segment and the largest privately-owned express logistics business, has led the way in investing in its own aircraft (other privately-owned companies utilise charter flights from airlines)

Whilst there are a number of well-known players in the industry, just four providers (EMS, SF-Express, Shentong Express and Yuantong Express) now make up almost two-thirds of the domestic express delivery market. However, whilst consolidating, China’s express logistics industry can still be characterised as a fragmented market. There are hundreds of small-scale (sometimes unlicensed) delivery businesses operating across the country. Smaller firms focus on regional offerings, often focussing on servicing one province or one district with business expansion limited by capital.

The domestic industry is facing disruptive change

We see six major trends affecting the market dynamics of China’s express delivery logistics industry:

1. Increasing customer dissatisfaction with quality of domestic services is providing scope for investment that can deliver differentiation

The express logistics industry has problems with theft, delays, lack of quality talent and advanced technology, all of which culminates in poor perceptions of service levels and complaint rates have increased massively (by 200 per cent during 2011) as the industry as a whole has struggled to deliver on service expectations. To improve the logistics industry, Chinese officials have issued the 2009 Plan to Adjust and Rejuvenate the Logistics Industry pushing for higher standards of service, innovation and efficiency.

However, a fundamental driver for the lack of quality service is lack of capital; smaller firms particularly do not have access to adequate capital for the development of technology and the personnel needed to consistently deliver a higher standard of service.

2. Consolidation pressures are increasing

The logistics industry will continue to see more M&A activity driven by a combination of regulation calling for integration of resources of large and small firms, and a competitive environment where larger firms are squeezing out smaller players and bringing innovation to the industy.

3. Ongoing organic investment is providing capacity for growth

The industry is seeing substantial organic investment. These investments range from aircraft and vehicles to the geographic expansion of the warehouse footprint.

4. Experienced new competitors are gaining access to the domestic logistics industry

The express logistics market is seeing signs of liberalisation, bringing more competitors to the market. The Vice President and Secretary General of China Express Association indicated at the 2011 China Express Forum that the China State Post Bureau plans to further liberalise the market by allowing foreign enterprises to enter the domestic delivery segment of services. In September 2012, UPS and Federal Express were granted licenses for domestic delivery.

5. Emergence of online retailing has increased demand for better logistics services

More and more Chinese consumers are shopping online or by mail order. It is thought that c.40 per cent of China’s express delivery volume comes from e-commerce delivery, with further strong growth expected.

The emergence of online e-commerce firms such as Alibaba, Taobao and 360.com at scale has also transformed the need for reliable fulfilment. E-commerce firms are now entering the express logistics market directly by developing in-house logistics platforms seeking to ensure consistency and reliability in fulfilment. For example:

- Alibaba announced in January 2011 that it planned to invest RMB 30 billion in building a nationwide chain of warehouses to accelerate delivery of products. Alibaba has subsequently taken equity stake in Stars Express in 2010, a move that will allow Alibaba to develop an in-house logistics arm.

- Liu Qiangdong, CEO of 360buy, also stated in 2011 that the company planned to invest more than RMB 10 billion in building logistics centres over three years.

6. Ownership structure of domestic players are shifting from franchise model to corporate-owned model

Franchising is currently the dominant operating model in China, and is widely used by top domestic players with 60-80 per cent of companies in the industry operating a franchise model. The model reduces risks borne by the company and the capital required for expansion and therefore supports rapid network expansion.

However, poor control over franchisees results in duplication of resources as each franchisee grows its own business independently and delivers inconsistent levels of service. Some companies are now seeing the challenge of managing franchisees across the country and are considering taking back direct control. Notably, SF-Express, Shengtong, Yuantong, TTK and Yunda started out using the franchise model but have since been buying back franchisees.

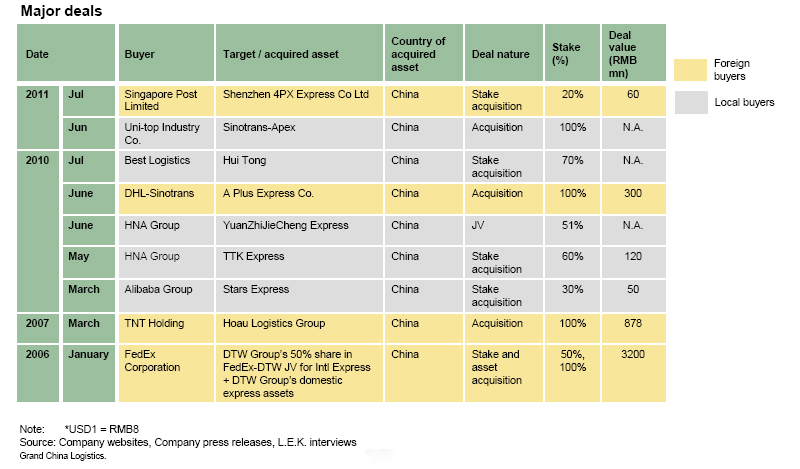

M&A being used as a route to scale

Most recent deal activity has been by trade buyers intent on expanding their footprint and service offer. Foreign players have been attempting to gain some access to the highly regulated and fast growing domestic segment. Domestic players, on the other hand, purchase other domestic firms to expand their geographic capabilities and improve technology and service levels.

Figure 2: Major deals (2006-11)

However, on closer inspection this set of deals poses a number of intriguing questions, including:

- Why are there so few deals for a sector that is expanding and consolidating so fast? There is believed to be significant interest and capital to fund transformational transactions

- Why are the recent acquisitions mainly done by strategic buyers and not by financial investors?

- Why is there no outbound investment from China?

We see a number of reasons for the limited number of deals in this sector:

- With the government injection of funds and loans, the largest domestic firms have been able to access relatively cheap capital through government and bank loans. As the market continues to develop and the role of government loans decline, the role of capital markets and private equity as sources of capital will increase.

- Smaller firms without large geographic reach are often funded by individual owners or franchisees who have yet to prove to financial investors the scalability/strategic defensibility of their businesses.

- The franchisee ownership model creates difficulties in driving post-M&A integration and expansion. This issue has observed in major domestic, private express companies developed from small start-ups and expanded via franchising or sub-contracting. Depending on the terms of the franchise agreement and structure of incentives, acquirers may not gain a good level of control of the business via acquisition. Moreover, poor management quality of franchisees or sub-contractors has made negotiations and plans for control and operations post-acquisition difficult. Anecdotal evidence suggests this has contributed to the failure of several deals.

- Finally, the express logistics industry can be a capital-intensive industry that requires large upfront investment and yet the accounts receivable cycle is long. With a lengthened cash cycle, any loss of continual injection of investments would cause liquidity issues, creating a high risk of default.

The logistics industry may seem on the surface a highly protected and capital-intensive industry. However, the industry also offers investment opportunities as better-quality logistics services will remain much in demand in China and there is room for both financial and trade investors to add value.

How might financial investors add value?

As well as the trade deals, many express companies are reportedly also in discussions with financial investors keen on investing in the sector. We see significant potential for financial buyers to add value and achieve mutual benefits from the deal:

- Contribute to a clear strategy for conquering a distinctive segment whether it be via organic growth, bolt-on acquisitions or transformational deals

- Create a more efficiently-run corporate structure to enable an effective sale to trade buyer

- Participate in consolidation negotiation process involving under-valued assets

- Provide expertise and financial tools to mitigate the asset and growth-investment cycle

- Invest in and develop an asset in a compelling niche (e.g., new technology and processes, IT systems, cold chain, medical and pharmaceutical delivery, etc.) likely to be of interest to a scale buyer expanding its service offer

- Facilitate overseas expansion, as in other sectors in China

What should investors consider before investing in a logistics company?

There are a wide range of issues to consider before committing to an investment in a Chinese express logistics company, including:

- What are the regulatory restrictions for investors, particularly foreign buyers?

- What is the growth potential of the target, both domestically and internationally?

- What is the fastest and most effective way to expand the network?

- Who are the logical partners for the investee?

- Specifically, are there good potential bolt-on targets from within this fragmented industry? What are the risks in pursuing further bolt-on acquisitions? How can these risks be mitigated?

- How will the rapidly changing competitive landscape of the logistics industry affect the target’s performance in the future?

- What will be the winning business model(s) in the medium/long term? Can the investee credibly transition to a winning model?

About L.E.K. Consulting

L.E.K. Consulting is a global management consulting firm that uses deep industry expertise and analytical rigor to help clients solve their most critical business problems. Founded more than 30 years ago, L.E.K. employs more than 1,000 professionals in 21 offices across Europe, the Americas and Asia-Pacific. L.E.K. has been on the ground serving clients in China since 1998. L.E.K. advises and supports global companies that are leaders in their industries – including the largest private and public sector organisations, private equity firms and emerging entrepreneurial businesses. L.E.K. helps business leaders consistently make better decisions, deliver improved business performance and create greater shareholder returns. For more information, please go to www.lek.com.

Michel Brekelmans is a Director with L.E.K. Consulting and based in L.E.K.’s Shanghai office. He has 15 years’ experience in strategy consulting with L.E.K. Consulting, of which 10 years is in Asia. Michel has worked on over 140 strategy, M&A and performance improvement projects and focused much of his time working for clients in the aviation, tourism and retail sectors. For more information, please contact Michel at m.brekelmans@lek.com.

Stephen Sunderland is a Director in L.E.K.’s Strategic Transportation Practice, where he has played a key role in L.E.K.’s work in the transportation and logistics sectors. He has over 10 years of strategy consulting experience, working with major corporate, public sector, and financial investor clients. For more information, please contact Stephen at s.sunderland@lek.com.

Recent Comments