What are the factors that could influence the outcome?

Following the first round of negotiations for the EU-China bilateral investment treaty (BIT), Gabriela Matei from Hill+Knowlton Belgium takes a look at some key factors that could influence the overall outcome of the agreement.

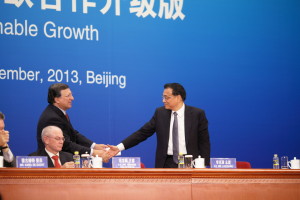

The first round of negotiations between the European Union (EU) and China on a BIT took place in Beijing from 21st to 23rd January. For the EU, it is the first ever investment agreement negotiated by the European Commission on behalf of its 28 member countries. While from a procedural perspective this is new territory, the BIT does not lack ambition. Indeed, in November 2013, upon the launch of the talks, the two sides pledged to increase bilateral trade from around USD 580 billion to USD 1 trillion by 2020. The deal would also provide a secure and predictable legal framework to investors in the long term. Typically, investment treaties aim at securing the same rights and advantages for foreign investors as for domestic ones, e.g. protection against expropriation without compensation or discriminatory legal treatment by the host country compared to local companies.

At present, EU-China trade amounts to over EUR 1 billion a day. While the EU is China’s largest trading partner and China is the EU’s second largest after the United States, investment flows are still relatively low by comparison. Chinese foreign direct investment soared following the outbreak of the financial crisis in Europe but EU investment to China has decreased despite the EU becoming the largest foreign investor in China.

At present, the EU believes it is premature to discuss a comprehensive free trade agreement with China. Instead, adding a market access component to the BIT seems the best vehicle to improve access to the Chinese market (and contribute to re-launching the European economy), although this will probably also be one of the most difficult elements in the negotiations.

Controversies and expectations

Does the joint push for the BIT mean that the negotiations will be easy? Not at all. As a rule, there are controversial aspects to all investment agreements, because both parties bring an agenda filled with demands from their respective constituents and, ultimately, a compromise has to be found that is endorsed domestically. On the EU side, the outcome of the negotiations will have to be ratified by the European Parliament whose members are already voicing their expectations in an attempt to put pressure on the European Commission negotiators. Human rights and sustainable development are high on the agenda. Equally, internationally recognised corporate responsibility standards form part of the EU’s mandate. Intellectual property recognition and enforcement is another prickly item. But two specific issues draw most attention in the debates in Brussels: first, the reform of Chinese joint-venture requirements for foreign investors and the elimination of what is perceived as unfair competition between state-owned and privately held enterprises; and, second, the investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) process.

The joint-venture requirement frustrates a number of EU investors, as no such conditions are placed on Chinese companies in Europe where there are no limits on foreign company ownership. In that respect, European investors expect a lot from the Shanghai Free Trade Zone. It is hoped that, if successful, the Zone will increase confidence from those who until now were hesitant to move into China due to an arguably restrictive climate.

Dispute settlement mechanisms—which enable companies to directly bring cases against the state in which they have invested before an arbitrational tribunal—are part and parcel of existing investment treaties. Some non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and political groups in the European Parliament have expressed concerns that this mechanism could undermine existing social, health or environmental legislation if it were to qualify as a barrier to investment. These groups claim that only state-to-state dispute settlement is appropriate in trade agreements and that private parties should not be granted the means to attack legislation in place in the country where they are vested. In turn, the European Commission has gone to great lengths to explain that the ISDS will by no means allow for the abolition of regulation through arbitration, but that it could lead to the award of damages in the event of a breach of the investment agreement.

A year of changes

This year will see major institutional changes in Brussels. In May, a new European Parliament will be elected. Thereafter, the President of the European Commission, the College of Commissioners (including the Trade Commissioner) and the President of the European Council will be appointed. The outcome of the elections and the new leadership of these institutions may lead to different policy priorities, as well as a change in approach to the BIT negotiations. In any event, because of the focus on internal political developments, the EU political leadership will have less time to debate the technical details, and much will be left to the officials involved in the negotiations. Even so, they are bound by the negotiating mandate they received from the EU member states.

As for China, the Third Plenum in November set expectations for deep economic reforms in the coming years. The plenum called for economic transformation through giving more power to the market and limiting government. The market is to be given a ‘decisive’ role in the allocation of resources, an upgrade of the ‘basic’ role described in previous plenums. In the minds of many European businesses and investors, this has created expectations and hope for better market access and a regulatory environment compatible with international treaties.

That said, in the past, EU countries have held diverging views depending on where their commercial interests lie. Traditional, free-trade-minded countries, such as the UK, the Netherlands and the Scandinavian states, focus on market access but are also very welcoming towards Chinese investors. Even in countries traditionally more sceptical, where national safeguards remain very strong, the focus on growth and jobs during a precarious economic upturn has contributed to a more positive environment. Reciprocity of investment conditions has become the mantra.

It is also important to mention that, according to recent polls, the European elections could well result in a strong presence of eurosceptics or outright anti-EU representatives in the Parliament. Although that would probably not affect the clear majority of the leading political groups (the Christian Democrats and the centre-left), the presence of parliamentarians who are opposed to free trade and who advocate for protectionist measures and restrictions at borders will certainly colour the discussions. This is not unimportant in light of the fact that the European Parliament needs to approve the BIT once the negotiations are concluded.

Can business influence the BIT?

As the talks advance, both parties—the EU and China—will seek support from their economic backers. But business could do more to ensure a positive outcome. On top of providing respective negotiators and political leaders with information to bolster the agreement, investors and companies should seek support, or at least understanding, for the positions they wish to be taken into account by the other camp. Chinese companies would do well to form business platforms to engage with industry counterparts in Brussels, as well as with EU officials and members of the European Parliament. All the more so since personnel changes following the May elections will see many new faces take the stage. They will no doubt want to learn about the views of Chinese and European businesses alike on how to overcome investment barriers and reach a mutually satisfactory outcome for the negotiations. All parties would benefit from informed debates and decisions. Those who stand to win the most from the treaty would benefit from understanding and explaining both sides’ points of view.

Hill+Knowlton Strategies is an international communications firm with 88 offices in 49 countries. With 2,000 consultants worldwide, we work for more than 185 of the Fortune 500 and are the leading consultancy in rapidly-developing markets. In mainland China, our offices in Beijing, Chengdu, Guangzhou and Shanghai serve a large number of domestic and international clients. We also have a presence in several 2nd tier cities.

I am not sure where you are getting your info,

but good topic. I needs to spend some time learning more or understanding more.

Thanks for magnificent information I was looking for this info for my mission.