Healthy China 2030 and its effect on the future of healthcare development in China

Healthy China 2030 and its effect on the future of healthcare development in China

Medical advances have taken place rapidly since the onset of globalisation, but while China has made some strides in healthcare there is much that needs to be done. Although Healthy China 2030 has been promoted as the initiative that will push domestic healthcare into the 21st century, there are a litany of health-related problems that still need to be tackled. Dr Eduardo Yoshida, from Global Doctor China, outlines what can be done to make China’s medical system more flexible and sustainable.

The World Health Organization (WHO), proposed a definition, linking health to well-being in terms of “physical, mental, and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease and infirmity”.[1]

China has operated, in many ways, on the foundations of ancient cultural traditions despite profound global changes in society and the economy. In order to retain cultural traditions while adapting to the rapid changes in the global environment, China has tried to creatively transform traditional Chinese medicine, and promote the domestic development of Western medicine.

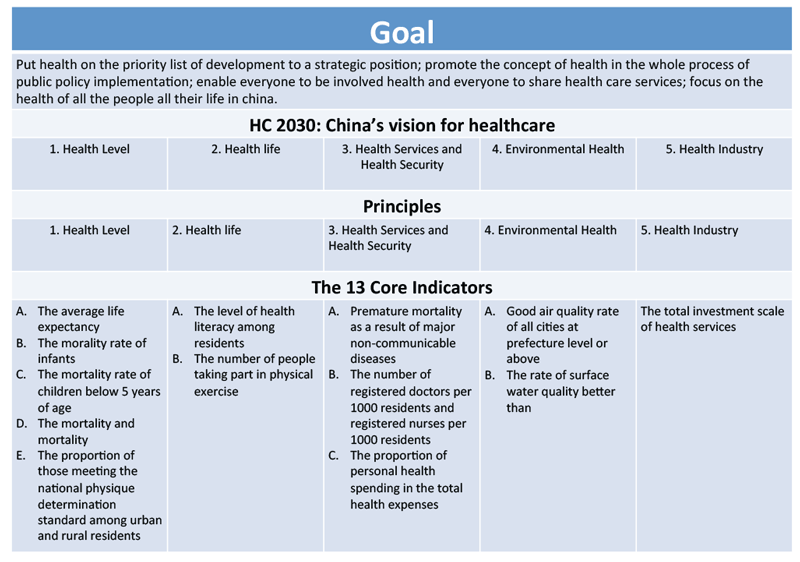

On the 19–20th August 2016, the China National Health and Wellness Conference was held in Beijing. Both President Xi Jinping and Premier Li Keqiang attended the conference and delivered important messages on healthcare. The Healthy China 2030 initiative was presented as the action plan for the next 14 years, with its goal being the improvement of 1.3 billion people’s health that live in China.[2] Five specific strategies were outlined in Healthy China 2030 to improve healthcare nationwide, including: controlling major risk factors, increasing the capacity of health services, enlarging the healthcare industry, and perfecting the health service system. These strategies are themselves based on four core principles, which are health priority, reform and innovation, scientific development, and justice and equity. These core principles were assessed using 13 indicators by the Central Politburo of the Communist Party of China. The assessment results will be reported in 2020 and 2030.

After years of effort, a basic national health insurance system has been created and remarkable progress has been made in reforming the healthcare system. As a result, improvements in healthcare and the environment—with some beneficial changes in air and water quality—have been seen. Despite these recent improvements, some serious health-related problems still exist, including: industrialisation and urbanisation; an ageing population; continuous changes in disease spectra; worsening ecological conditions; and people’s unhealthy lifestyles.[3]

What are some new areas of Healthy China 2030 that have yet to be explored?

Due to China lagging behind in healthcare, the government must set clear and effective policies to effectively govern and enforce health system reforms. One area that requires more attention is primary healthcare. Currently, the Chinese healthcare system is struggling to keep up with rising medical costs, especially for serious illnesses, work-related injuries and the elderly.[4] The social and economic transformation of the population, including improved life expectancy, population migration from rural to urban areas and easing of the one-child policy in 2013, have resulted in a sharp increase in demand for medical services which threatens the healthcare system’s ability to provide treatment on an equitable basis.

What do you think the chances are of successfully expanding healthcare to all citizens in China?

Healthcare development is a dynamic process that combines flexibility and strength in order to ensure that the system is adaptable and sustainable. Providing healthcare to all Chinese citizens is possible, but work must be done by the citizens themselves to ensure there is a healthy environment and that they are health literate.

A well-educated and health literate population is now possible with advances in technology and easier access to information from the media. This increase in easily accessible medical information means that people are now in a better position to take responsibility for their own health. Organisations that provide opportunities for cross-cultural medical exchanges can be vital to healthcare reforms and can contribute to educating a populace on health issues. Given the complexity and time required for the development of a fully functional national healthcare system, it would be prudent to utilise all existing health resources. Ensuring a healthy populace is not just about healthcare education, but going above and beyond pharmaceutical interests to push for medical innovation and compliance with existing international protocols.

[1] Grad, F.P., 2002, The Preamble of the Constitution of the World Health Organization, Bulletin of the World Health Organization, vol. 80, no. 12, p. 982.

[2] Liu, Wei, Health sector, the next big industry, China Daily, 26th October 2016, <http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2016-10/26/content_27181681.htm>

[3] Statistics and indicators for the post-2015 development agenda, UN System Task Team on the Post-2015 UN Development Agenda, viewed 2017, <http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/policy/untaskteam_und/them_tp2.shtml>

[4] China spends trillions on health care improvement, China Daily, 29th April 2016, <http://usa.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2016-04/29/content_24952168.htm>

Dr Eduardo Yoshida is an extensively qualified medical physician with 20 years working experience in both hospitals and clinics and is currently the medical director of the Global Doctor Nanjing Medical Centre. Global Doctor China is a healthcare group started in 1999. It has a 24-hour call centre and 10 medical centres with multi-lingual medical teams. The group offers outpatient primary care, corporate healthcare services and medical assistance. It also provides medical access to Hong Kong and worldwide medivac.

Recent Comments