Due to the low cost of raw materials and labour, Chinese-made products now reach all corners of the industrialised world. The safety of consumer products has become an increasingly sensitive and much maligned topic, and deservedly so. Comprehensive quality standards are put in place in all regions of the world and are often amended in response to technological and economic developments in an attempt to remove potential trade barriers.

Due to the low cost of raw materials and labour, Chinese-made products now reach all corners of the industrialised world. The safety of consumer products has become an increasingly sensitive and much maligned topic, and deservedly so. Comprehensive quality standards are put in place in all regions of the world and are often amended in response to technological and economic developments in an attempt to remove potential trade barriers.

In the article below David Chen, a senior manager of overseas operations at Centre Testing International Corporation (CTI), gives an overview of consumer product safety, the complications facing Chinese manufacturers and the matters in which globalisation has influenced the standardisation industry. Despite tightly controlled regulations for consumer product safety in China he explains that enforcement is often a key issue.

Although it is commonplace for a single consumer product manufactured in China to be sold across the European Union and in North America, end users are most likely unaware of the complexities facing retailers in trying to comply with the different quality standards throughout the supply chain.

Individual countries and regions are regulated by different standards for comparable products; the obligation lies with the manufacturer to comply with each of them. Although similar in scope, as well as the analytical instruments used in its testing methodologies, international standards differ through their restrictions on test items, permitted concentration values and functional properties, with Chinese standards generally being less strict in comparison to Western equivalents.

Quality standards in China are subdivided into four categories: national, industrial, provincial, and enterprise standards. National standards (GB) are the most prevalent and administered directly by the General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection, and Quarantine (AQSIQ). Local testing laboratories are accredited by the China National Accreditation Service (CNAS) and China Metrology Accreditation (CMA); test reports bearing the mandatory CNAS and CMA marks verify a document’s legality in China with respect to the compliance of the product(s) in question. Further domestic and international marks may only be applied on a report by laboratories and organisations recognised by the corresponding accreditation bodies. In other words, in the world of quality testing, audit and certification, accreditations denote technical proficiency.

Using an electronic toy car as an example, the testing begins with its physical and mechanical properties, such as durability, fatigue and failure analysis, followed by flammability and toxic elements. These tests all belong to subsets of national and regional level regulations: GB (China), EN (EU) and ASTM/CPSIA (USA). The product must also comply with the equivalent standards of all of the other markets it will be exported to. In addition, toy regulations also include testing for electrical functions, concentration of phthalates, and many more. Phthalates—a commonly applied plasticiser used in juvenile products to increase the ductility of polymer materials—has been shown to have adverse effects on health.

Depending on the composition of raw materials involved in producing the toy car, a more suitable substitute for hazardous chemicals may be found in the Restriction of Hazardous Substances (RoHS) directive; RoHS first took effect in the EU in 2006 with respect to electronic and electrical equipment placed on the markets of EU member states. Concentrations of six chemical substances classified as hazardous are restricted: Lead (Pb), Mercury (Hg), Cadmium (Cd), Hexavalent Chromium (Cr6+), Polybrominated Biphenyls (PBB), and Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDE).

Depending on the composition of raw materials involved in producing the toy car, a more suitable substitute for hazardous chemicals may be found in the Restriction of Hazardous Substances (RoHS) directive; RoHS first took effect in the EU in 2006 with respect to electronic and electrical equipment placed on the markets of EU member states. Concentrations of six chemical substances classified as hazardous are restricted: Lead (Pb), Mercury (Hg), Cadmium (Cd), Hexavalent Chromium (Cr6+), Polybrominated Biphenyls (PBB), and Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDE).

China’s RoHS (officially known as the Administrative Measure on the Control of Pollution Caused by Electronic Information Products) was derived from the EU’s RoHS and adopted at a later date, with restrictions imposed on the same six substances. The two scopes differ though: The EU’s RoHS covers all electronic and electrical equipment with an appendix listing exempted items; China’s RoHS is accompanied by a catalogue listing the individual categories of products that it applies to—electronic toy cars are not among those listed.

There is no labelling necessary for EU RoHS qualification, with document checks and test reports often conducted through customs. Conversely it is obligatory in China for all items contained in the RoHS catalogue to be clearly labelled and self-declared on the product’s packaging, indicating the existence of hazardous substances, along with the duration in years before these substances will start to discharge into the environment. This illustrates the similarities and also the discrepancies found when comparing Chinese regulations to the existing international ones from which they are adopted, which is a common and reoccurring theme throughout product safety compliance.

Increased demand from foreign markets not only induces competition, but also complicates the procurement process. It cannot be ignored that the manufacturing boom in China is unquestionably driven by cost control. In order to gain a competitive advantage manufacturers and raw material suppliers have in known cases resorted to unethical practices. On the positive side, however, Chinese regulations are gradually being brought into line with international ones, paving the way for stricter levels of compliance further down the road.

In a perfect world there would be a single set of internationally recognised regulations, but this is not the case and is highly unlikely to ever come to fruition. It is possible for multiple regulations on chemical concentration levels to be cross referenced and combined but it is not possible to do this with physical, mechanical and flammability testing. Different functional features among products result in different test methods and requirements. In addition to these complications large multinational companies may also prefer to have their own internal standardisation systems, although these may already take overlaps of regulations into consideration.

If a product is potentially hazardous—to humans or the environment—as a result of its manufacture, and is intended for release into the EU market in quantities of one tonne per year or higher, it must be officially registered with the European Chemicals Agency. Registration must also include safety data sheets pertaining to the Registration, Evaluation and Authorisation of Chemicals (REACH) regulation.

REACH is accompanied by testing restrictions through the chemical substances of very high concern (SVHC). SVHCs are a group of chemical substances defined to be carcinogenic, mutagenic, toxic for reproduction (adverse effects on fertility or sexual function), or persistent and bio accumulative. China’s adaptation of REACH features distinctive characteristics once again. It mandates new substances, including those used as intermediates and irrespective of its annual tonnage, to be notified with the Chemical Registration Centre of the Ministry of Environmental Protection.

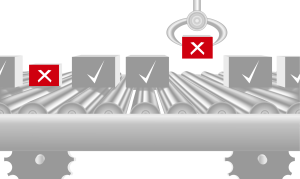

Countless products worldwide are also subjected to certification prior to market entry; the CCC (China) and CE (EU) marks for instance are compulsory for affected products placed on those markets. In comparison with foreign countries there exist many imperfections detailing China’s safety and quality management systems. Certification of a product is not in place to change the consumer’s perception of its quality and safety at macro-level. Analysing on a micro-level though, certification may improve a product’s compliance, conformity to management systems and market entry thresholds, consequentially improving the consumer’s confidence in specific products. The long-term development of China’s RoHS will speak loudly on this matter if products placed on the Chinese market are one day mandated to bear the CCC mark. It should be noted, however, that at the time of writing, although the blueprints are in place, China’s adaptations of RoHS and REACH are yet to be made mandatory.

With all such regulations in place, why does the label ‘Made in China’ continue to be associated with low-quality goods and negative connotations? New regulations are routinely enforced or revised to become increasingly stringent but implementation is often not met with the same sense of urgency. The poor performance levels of products manufactured in China, when compared to foreign imports, imply not only low quality but also low levels of compliance. For now, Chinese state and local government agencies, retailers and, most importantly, manufacturers, must continue to cope with this stigma.

It could be argued that through globalisation and public exposure perceptions of the ‘Made in China’ tag have improved slightly in recent years. Nonetheless, further, significant improvements to Chinese-produced commodities are required and these products will continue to be subject to close scrutiny by the rest of the world for the foreseeable future.

Perhaps most importantly of all, it is imperative for a nation of 1.3 billion people to increase the social awareness of the safety of its consumer products, only then will there be unequivocal commitment to quality from manufacturers and exporters.

David Chen has extensive experience overlooking partnerships with international retailers and supermarkets for Centre Testing International Corporation (CTI). CTI is a Chinese domestic third party product testing, inspection, audit, and certification organisation. CTI, together with its subsidiaries CTI Certification and REACH24h Consultant Group, forms a ‘one-stop’ service network for its clients covering each step of the supply chain. For more information please visit www.cti-cert.com, www.cti-cert.org, www.reach24h.com.

TAGS: consumer goods, consumer rights, legislation, manufacturing, standards

Recent Comments