Emerging stars in the booming private healthcare sector in China

China’s overburdened public healthcare system has led to private hospitals playing an increasingly key role. Shuai Yuan, co-founder and co-CEO of Care Alliance, describes how post-acute healthcare providers can help make China’s health system more sustainable.

In China, there are currently more than 200 million people over 60 years old, and this number is expected to double in the next three decades. This is creating an elderly population that is larger than the total population of the United States. As the elderly are more susceptible to sickness, an ageing population creates the need for a more robust healthcare system. In recent years, a larger part of China’s population has been made up of those that came into adulthood in a more modern China, and when it comes to healthcare quality they want to ensure they receive the best. The increased demand for high-quality healthcare services by this modern generation, and the necessity for an increase in the availability of treatment for a quickly ageing population, has driven the Chinese Government to encourage the development of private hospitals.

As part of China’s five-year healthcare reform road map from 2015–2020, the government is seeking to increase private hospital participation in order to alleviate pressure on the under-resourced public healthcare system. Private hospitals are garnering long-term benefits from healthcare reform, leading to an increase in private hospital coverage. Private hospitals provide an alternative for people who are no longer satisfied with subpar service and care in public hospitals – they attract patients to their hospitals with their premium services, accessibility and more modern environment. Thus, among different types of private hospitals the most immediate beneficiaries are the more service-orientated specialty hospitals with lower medical risks, less reliance on doctors, lower operational hurdles and more replicable business models. Cosmetic surgery and obstetrics and gynaecology are the two medical specialties that have the largest number of private hospitals – over 90 per cent of these specialty hospitals are private. Orthopaedics, otorhinolaryngology and ophthalmology have also seen a rise in private operators.

Number of Hospitals in China, Public vs Private

Source: WIND

Source: WIND

With the rapid growth of private hospitals, a lesser- known but well-positioned category of specialties is rapidly emerging that is known as post-acute medical services. This can include rehabilitation centres and long-term nursing facilities. These facilities not only share the same traits found in private hospitals such as low medical risk, low operation difficulty and high scalability of its business model, but they also follow the same healthcare reform guidelines and serve to meet the growing demand from the elderly for access to healthcare.

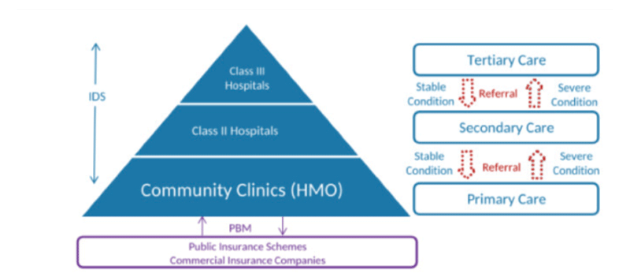

In China, the allocation of medical resources to various medical institutions is severely imbalanced. China’s hospital system is primarily broken up into three distinct tiers as follows:

1. The top tier is class III, which includes large-scale hospitals that typically have the best doctors, facilities and resources for research and development.

2. The next tier down is class II which is also known as an above mid-sized hospital.

3. Lastly are the class I ranked hospitals that are considered primary clinics and mainly offer community healthcare services.

In 2016, class II and III hospitals accounted for only 35 per cent of the total number of hospitals, but contributed to 87 per cent of the total patient visits, indicating that these hospitals were operating at over capacity. The stress is so great on these classes of hospitals that additional beds are placed in corridors. Subsequently, efficiency problems arise: long queues, overstretched doctors, inadequate attention spent on patients, and diagnoses made with the minimum amount of time allowed. One key component of the government’s healthcare reform is the establishment of a tiered health service system, where patients are classified into different tiers and transferred by referrals to allow for a more efficient allocation of medical resources.

Ideal Triple-tiered Health Service System

Source: Morgan Stanley: PBM – Public Benefits Manager, HMO- Home Management Organisation

Source: Morgan Stanley: PBM – Public Benefits Manager, HMO- Home Management Organisation

The purpose of post-acute healthcare providers aligns perfectly with China’s healthcare reform. They take care of patients referred from over-crowded class III hospitals so these same hospitals achieve higher bed turnover and save beds for patients with more severe conditions in need of stronger medical support. This increases service capacity without having to invest into additional hospital beds and facilities. For an elderly person who requires only basic medical support but long-term nursing care, they would be more suited to a long-term nursing facility than a large general hospital.

Despite the benefits of having more efficiently allocated medical resources, the tiered health service system will not work without the endorsement of large general hospitals. In China, the government insufficiently investing in public healthcare has led most large general hospitals to essentially be responsible for both revenue and incurred costs. Conventional thinking indicates that large general hospitals lack the interest to follow the tiered system, which restricts their patient sources and limits their financial gains.

Interestingly, the data suggests otherwise since large general hospitals could be financially incentivised to transfer patients with a lesser need for medical attention down to lower-tier facilities. The following is a case that supports the economics behind complying with a tiered healthcare system.

The payment curve of a typical orthopaedic surgery patient with a stay of 10 days, suggests that approximately 70 per cent of the patient’s total medical expenses happens in the first three to four days. While in the remaining six to seven days of their hospital stay, patients are usually paying much less since they are mostly on bed rest to recover. In this scenario, if a large general hospital were to discharge the patient on day five of his normal 10-day stay, leaving the recovery time for post-acute facilities, then the hospital could take another patient, which would double their revenue during that same five-day period.

Of course, this model depends on two key assumptions. First, large general hospitals need to quickly admit a new patient in a severe enough condition to fill the bed that the previously discharged patient left empty. Second, large general hospitals need to fully understand and identify how they can measure financial gains by taking advantage of the tiered process. The reality is, that most general hospitals are still reluctant to let go of the more immediate source of profit and often hold onto patients that could have been discharged. As more and more hospitals test the water and see improved financial results, they will eventually be incentivised to start supporting the tiered health service system.

On the patient side, they can now resort to post-acute facilities in order to address their functional and chronic problems that have been previously neglected at large general hospitals. Surgeons are too busy to pay sufficient attention, as many see a successful surgery as the end of their job. Post-acute facilities provide more than clinical treatments. While commonly overlooked, the psychological and sociological aspects of care and support from the medical staff are equally essential to a patient’s recovery as clinical treatment is. For example, rehabilitation hospitals focus on returning patients’ physical, mental and sensory capabilities to a normal condition. Rehabilitation can help a body achieve normal functionality through constant care, supervision and recovery techniques. Studies show that nearly 95 per cent of first-time stroke patients are able to have fully restored bodily functions if they receive timely rehabilitation intervention. Needless to say, as post-acute recovery tends to take much longer than clinical treatment, most newly-constructed post-acute facilities offer a warmer, more modern design with more patient-centric services that allow patients to have a much more enjoyable experience than in traditional public general hospitals.

One obstacle still remains, however, and that is patient awareness. Take rehabilitation for example. Conventional wisdom in Chinese culture suggests bed rest after surgeries and because of this, few people are aware of the need for rehabilitation. Same goes for long-term nursing facilities. It is traditionally a symbol of filial piety to attend to your own parents so most Chinese people are reluctant to send their parents to nursing homes, despite inconvenience and unprofessional care at home.

China is facing an ageing population and a rising demand for quality healthcare services. The government is wasting no effort in strengthening healthcare and building up the tiered health service system. Admittedly, such developments will take years to play out, but with strong government support, a proper incentive mechanism in the tiered service system, patients’ demand for better services and more holistic care, and the use of post-acute healthcare providers, these initiatives will ultimately become reality.

Care Alliance operates post-acute rehabilitation hospitals and clinics, geriatric hospitals and long-term nursing facilities. It is committed to promoting modern principles and practices as well as cultivating talents in post-acute care in China.

Recent Comments