Interview with Adam Dunnett, secretary general, European Union Chamber of Commerce in China[1]

When you first came to China in the late 1990s, did you foresee its rapid economic growth?

China’s gross domestic product (GDP) had already been growing in double-digits in the 1990s. This was considered more of a peculiarity at the time, with few people confident about the long-term trajectory of China. There were many uncertainties: massive state-owned enterprise (SOE) debt, high unemployment, concerns about social stability, and internal debates about China’s further opening up and accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO).

I remember The Economist had a cover around this time with an image of a magician pulling GDP numbers for China out of a hat, giving the impression that perhaps China’s growth was more magic than reality.

I can’t say I was certain about China’s future, but I didn’t understand why so many observers were so sceptical. Even many Chinese officials and scholars doubted China’s ability. I often heard the phrase “我们要向你们学习” [we must learn from you] and many self-deprecating comments about how China was still “落后” [backward].

However, it was an exciting period. The country was buzzing. There was always something new about to happen. A new shopping centre, a new airport, a new metro line, a new highway, a new investment.

I remember once standing on the 50th floor of the Capital Mansion building in Beijing and counting 50 construction cranes within sight. I remember thinking that the GDP numbers aren’t being over-reported, but under-reported.

So, I guess you could say I was actually quite optimistic.

Can you sum up the country’s progress in one sentence?

It’s been a constant, gradual transition of improved urban, material and individual well-being.

What would you say has been the key to China’s rapid growth?

The latent potential and demand were already there, it was more a matter of tapping into it. I would say there are five main elements, each uniquely significant in their own right, that paved the way for China’s rapid growth. First was the liberation of trade in the 1970s. WTO accession in 2001 both locked in and accelerated this process further by bringing down average import tariffs to 9.8 per cent and technically opening the services sector. Second was privatisation, starting initially in the 1980s with the contract responsibility system; it unleashed massive entrepreneurial market forces, moving China away from its originally planned economy approach to development. The third was increased foreign investment, which brought much-needed capital and technology. Fourth was government-led infrastructure development. Finally, China’s social and economic stability helped it weather the 1997 Asian financial crisis, the 2008 financial crisis, and the COVID-19 pandemic, and come back strongly. Markets are not perfect and the Chinese Government has played a critical role as well.

What’s your overall evaluation of China fulfilling its WTO obligations?

When China completed its transition period in 2006, we wrote: “China has successfully implemented the majority of WTO commitments on, or ahead of, schedule. However, European companies find that transparency and intellectual property rights (IPR) remain concerns of doing business in China”.

These were issues in 2006, and they are still very relevant today.

The WTO stands for freer trade, but this doesn’t mean the law of the jungle. It means trade that’s free from obstacles, including IPR theft, discrimination, government intervention, and a lack of transparency and predictability.

Back then we said that China often followed the letter of the law, but not always the spirit. As one Chinese reporter once commented to me, your definition of ‘transparency’, “predictability’ and ‘openness’ is just perhaps different than ours.

The power shortages across China in 2021 is a classic example of foreign businesses’ expectations still differing strongly with what China is prepared to offer.

How do you expect the role of international trade in China’s economy to change in the next two decades?

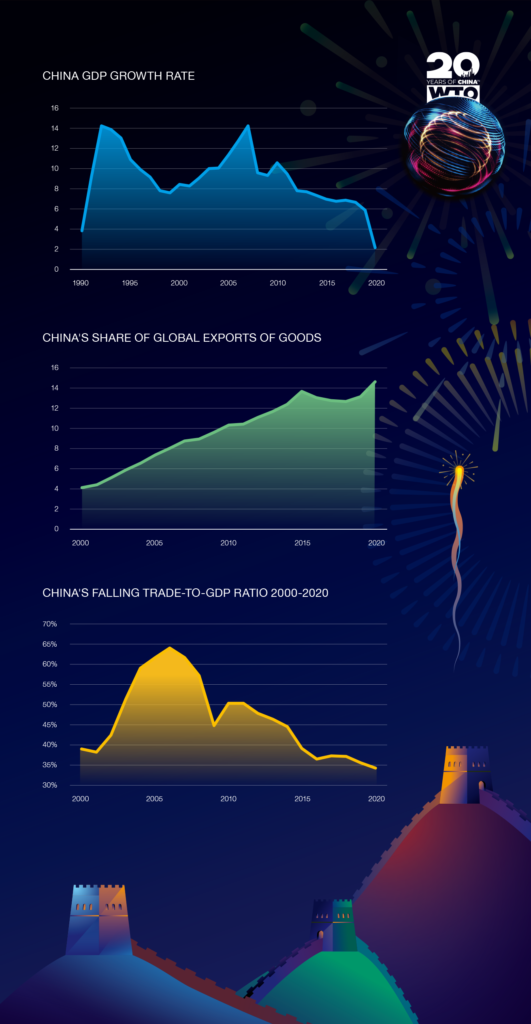

China was one of the biggest drivers and beneficiaries of international trade in the last two decades. In 2000, China only accounted for four per cent of global trade. Today, it accounts for 15 per cent. However, things are changing.

Global trade growth has slowed dramatically in the last ten years. Prior to the 2008 global financial crisis, growth of international trade typically surpassed that of GDP. However, in nine of the last ten years, international trade has grown more slowly than world GDP.

Trade also represents a much smaller share of China’s economic output today. It’s relatively less important to the Chinese economy and China seems just fine with that. China’s trade-to-GDP ratio peaked in 2006 at 64 per cent, falling to 34.5 per cent in 2020 as China moved towards increased self-reliance.

The focus on self-reliance in China’s 14th Five-year Plan is actually not new, but a continuation of past policies to acquire, digest and develop indigenous technologies. The United States-China trade war initiated under Trump has only served to convince the Chinese that this strategy is correct. This has always presented both an opportunity and a challenge for European companies. China’s focus on “secure and controllable” technologies means that international enterprises are forced to further localise their technologies in order to maintain access to markets and customers.

In January 2021, the European Chamber released Decoupling: Severed Ties and Patchwork Globalisation, which highlighted ‘trade decoupling’ as one of seven risks to the global economy. However, the European Chamber’s Business Confidence Survey 2021 showed that while trade decoupling was likely, companies would not decouple from an investment perspective. In fact, in the current situation, the survey results show that companies are five times more likely to onshore into China than to offshore.

Looking ahead, international trade will remain vitally important to supply chains, but it is unlikely to ever regain its former dominant position in China’s overall economy. Instead, the bigger opportunity for future economic relations is still expected to come from bilateral investment. This is why the European Union prioritised its negotiations with China on the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment over the last seven years, and why the European Chamber still hopes that this deal may one day be ratified.

[1] This interview is an abridgement of an article in The Japan-China Economic Journal <https://www.jc-web.or.jp/publics/index/781/0/>

Recent Comments