Leapfrogging for common prosperity

Can innovative collaboration help us face challenges around food security and climate change? What can we learn from China’s centrally-driven, digitally-connected, modern agricultural industrial parks (MAPs) that are revitalising its agricultural ecosystem at lightning speed? Johnny Browaeys and Soraya Kadra take a look at how the MAPs work, and how European companies can interact with them.

Agriculture, food security and climate change

As the country with the highest food consumption in the world, China’s food security has become a subject of global attention. China represents 20 per cent of the world’s population, but only nine per cent of the world’s arable land. Domestic production has nonetheless so far largely been able to meet China’s growing demand for food due to its rapid agricultural transformation.[1] For instance, China’s self-sufficiency ratio (SSR) of the three staple crops—rice, wheat and corn—was 98 per cent in 2018 and 95 per cent in 2019.[2]

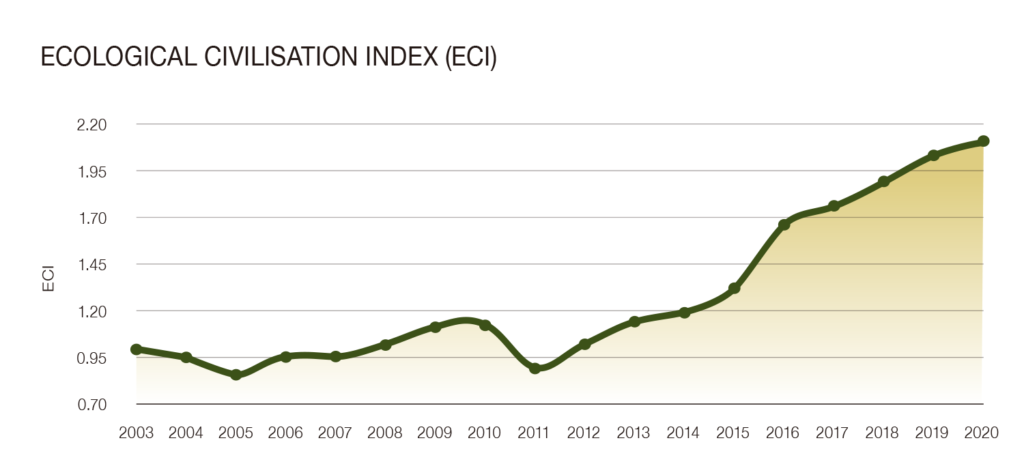

A slowdown of growth in grain yield to below population growth has been observed worldwide, signifying that natural limits have been reached and new agricultural approaches are needed. Moreover, land degradation and climate change are putting the SSR under pressure: the ratio of the world’s 54 top staple food products dropped from 94 per cent in 2000 to 83 per cent in 2010, and further still to 76 per cent for 2020.[3]

Rural revitalisation

In 2018, China issued a Rural Revitalisation Strategy to modernise agriculture and the rural economy fully by 2050. New schemes were issued, such as:

- Cang liang yu di (food storage in the ground), addressing current and long term production capacity including land regeneration; and

- Cang liang yu ji (food storage in technology), emphasising the role of technology in food security.[4]

The non-binding nature of China’s gross domestic product (GDP) growth target for 2025—as announced in its 14th Five-year Plan—and piloting of a new alternative indicator to assess economic growth—the gross ecosystem product (GEP)—is a turning point in assessing the economy.[5] GEP is a unique indicator that encompasses the value of a natural ecosystem’s goods and services,[6] as well as the depreciation of environmental assets, such as degradation of the biosphere.[7]

Agriculture 4.0

In February 2019, the Development Plan of Digitalisation of Agriculture and Rural Areas (2019–2025) set the basis for China’s Agriculture 4.0. The main characteristics of Agriculture 4.0 are ecologicalisation, socialisation and the Internet, as the intention is to use technology to ensure food security and rural revitalisation. This plan has five main tasks

- Build a basic data resource system.

- Speed up the digital transformation of production and operation.

- Promote digital transformation of management services.

- Strengthen key technology and equipment.

- Strengthen the construction of major engineering facilities.

The plan is also driven by three main metrics that need to double by 2025: the agricultural digital economy must account for 15 per cent of the sector’s value-add; the proportion of agricultural products sold online should hit 15 per cent; and internet access in rural areas should reach 70 per cent (FAO 2019).[8]

Modern technology strengthen the potential for innovation, optimise agricultural processes and can connect small/medium-scale farmers to the national ecosystem. For instance, agricultural drones—which can be used to spray pesticides—currently only represent two per cent of agricultural plant protection in China. The dominant force (90 per cent) is semi-mechanised electric sprayers, but the application of drones is expected to rise rapidly.[9] Additionally, China is the biggest agricultural e-commerce market worldwide, and is able to connect small/medium-sized farmers to the national market.[10]

Modern agricultural industrial parks (MAPs)

As part of this modernisation, the Chinese Ministry of Agriculture in 2019 approved more than 114 national MAPs, to facilitate the development of local smart agricultural business ecosystems and communities, including farmers, businesses and consumers.

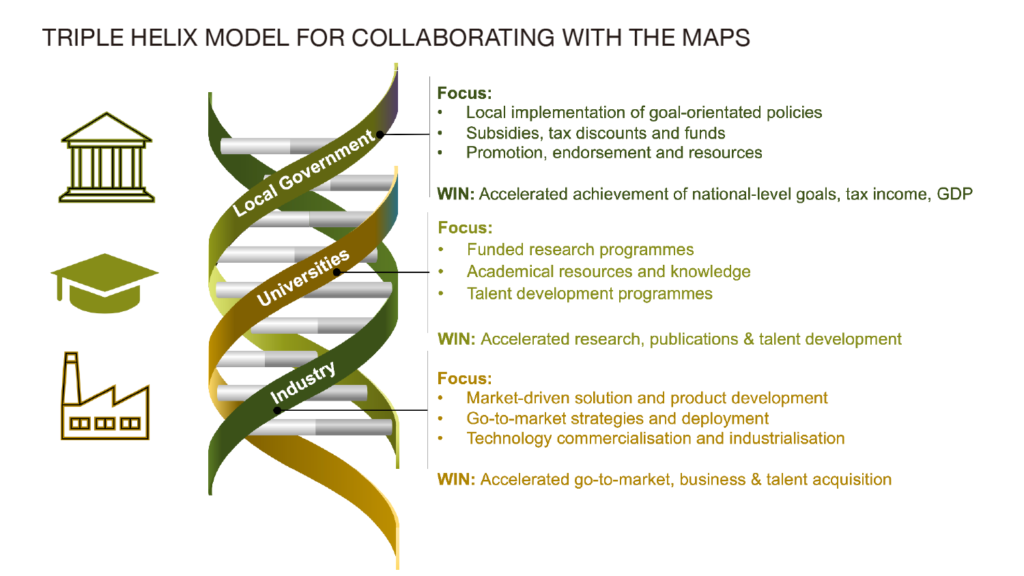

The MAPs provide a platform for the government, academia and industry to collaborate. In 2020, there were more than 250 MAPs, led either by the government (87 per cent), industry (9.7 per cent) or research institutes (3.3 per cent).

The shared objective is to grow sustainable business value chains, secure food resources, safeguard natural assets and serve all stakeholders. The MAPs aim to accelerate agricultural technological innovation and resource development, train modern farmers, and link government policies with industry and financial investments focussed on innovation.

Opportunities for European companies

European companies wanting to participate in this fast-developing market should strategically engage with the three key stakeholders: 1) the local government; 2) universities / institutes; and 3) state-owned enterprises / local companies / entrepreneurs. A company that is able to understand and contribute to a local government’s key performance indicators will become very attractive to them.

Companies that are already strategically engaging with the MAPs to roll out a nationwide go-to-market strategy are growing at lightning speed. Some of the most successful examples have developed new business streams from zero to over euro 0.5 bn in three years, even tripling revenues during COVID, profiting from the digitalisation drive.

Some companies work with the MAPs to help farmers increase profits and sustainability by improving soil health, reducing pesticides and fertilisers use, increasing crop yields and reducing water pollution. Others use blockchain technology to provide traceability and end-to-end visibility of fresh products from field-to-fork: consumers can scan a QR code on food packaging enabling them to see which farmer produced the goods where, as well as the product’s health and sustainability data. For example, the technology allows strawberries picked one day to reach consumers the following day, with all the production data provided.

A call for collaborative innovation: the story of Farmer Zhu in Henan

To see how MAPs can mitigate the effects of extreme weather, Farmer Zhu in Anyang, Henan, with 650 Mu (43 hectares) of corn, provides a case study. In mid-2021, his fields were flooded and his crops seemed lost. The MAPs team was called in and used satellite imagery to check where Farmer Zhu’s fields were starting to drain. They used drones to spray the plants there to protect them against diseases caused by the flooding, and biological stimulants to get them growing again after the waters had receded. Being able to combining modern technology with farming saved Farmer Zhu 65 per cent of his crop yield.

Similar solutions are being used to protect Europe’s wine industry, which is affected by climate change, and Dutch tomatoes that are being eaten by migrating insects. Meanwhile, the demand for new crop varieties that can better withstand drought is increasing rapidly. Collaborating to innovate will be spurred into a race against time to soften the impact of climate change.

Voices from the field

Chen Chunlan, who provides training at the MAPS centres witnessed how local farmers increased their sales conversion rate from a mere one per cent to 25 per cent using online agronomy training; enhanced plantation, crop protection and machinery equipment-handling skills; branding to attract consumers; digital sales tools; and shifting from revenue growth to profitable growth.

Asked for her recommendations for European companies, she replied: “Liaise with the MAPs and government agencies to understand how to promote your business. Learn how they collaborate with different stakeholders to serve the farmers and consumers. Find the common goal, shared values and use success cases to build trust.”

Chunlan also referred me to lyrics from an old Chinese song: “二月卖新丝,五月粜新谷” or “New silks are sold in February, new grain is bought in May”. This Tang Dynasty song is well-known for its expression of deep care and sympathy for the hardship of peasants’ livelihoods.

Acknowledgement of this hardship and of farmers’ importance to food security as climate change begins to show its impact may well be the main reason why President Xi Jinping sees the modernisation of China’s agriculture as key to common prosperity.

Note: This article is a follow-up to a 2019 Eurobiz article:China leapfrogging to a circular economy

Johnny Browaeys is the Shanghai chair of the European’s Chamber’s Environmental Working Group and chair of Seeder Clean Energy. As a corporate entrepreneur, he pioneered new businesses for Chinese, European and American companies in China and as an entrepreneur he nurtured five startups in the GreenTech space.

Soraya Kadra is an expert on Innovation and Circular

Economy at Seeder Clean Energy.

[1] Gulati, A., Zhou, Y., Hunag, J., Tal, A. and Juneja, R., From Food Scarcity to Surplus – Innovation in Indian Agriculture, Springer, 2021, <https://link-springer-com.brad.idm.oclc.org/content/pdf/10.1007%2F978-981-15-9484-7.pdf>

[2] Hu, Yiwei., Graphics: How China feeds its 1,4 billion people, CGTN, 23rd September 2019, <https ://news.cgtn.com/news/2019-09-23/Graphics-How-China-feeds-its-1-4-billion-people-KdLxOoA7x6/index.html>

[3] Hadano, T., Degraded farmland diminishes China’s food sufficiency, NikkeiAsia, 2021, https://asia.nikkei.com/Economy/Degraded-farmland-diminishes-China-s-food-sufficiency.

[4] Niu, Z., Yan, H., and Liu, F., 2020, Decreasing cropping intensity dominated the negative trend of cropland productivity in Southern China in 2000–2015, Sustainability, vol.12, no.30, <https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/12/23/10070/html#B7-sustainability-12-10070>, Huang, J. and Yang, G. (2016), Understanding recent challenges and new food policy in China, Global Food Security, vol.12, pp. 119-126.

[5] Liu, H., Liu, J. and You, X. (2021) Q&A: What does China’s 14th ‘five year plan’ mean for climate change? CarbonBrief.

[6] Ye, Y. (2021) GEP, a Green Alternative to GDP, Gaining Ground in China. Sixth Tone.

[7] Desgupta, P. (2021) The Economics of Biodiversity: The Desgupta Review. London: HM Treasury.

[8] Au, L. (2020) China looks to robots, big data to drive agriculture forward. Technode. https://technode.com/2020/01/22/china-looks-to-robots-big-data-to-drive-agriculture-forward/

[9] Gulati, A.; Zhou, Y.; Hunag, J.; Tal, A., and Juneja, R. (2021), From Food Scarcity to Surplus – Innovation in Indian Agriculture. Springer, <https://link-springer-com.brad.idm.oclc.org/content/pdf/10.1007%2F978-981-15-9484-7.pdf>

[10][10] Thomala, L. (2020) Number of Internet Users in China from 2017 to 2023. Statista.

Recent Comments