Can China’s peri-urban areas reverse recession and transform?

As China’s population has become increasingly urbanised, it is common for rural areas to find their young population depleted and that they are overlooked by most of the industries that are driving the economy forward. This is a scenario played out in unindustrialised regions across the world. The current preferred strategies for economic growth, with a heavy focus on technology and manufacturing, often do not address the challenges facing regional populations. Dereck Ji and Brian Yu of EY-Parthenon describe how an ‘aesthetic economy’—one that taps into the artisanal and cultural advantages of a region or locality—can offer alternatives for rural development.

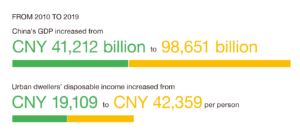

After years of reform, China’s national economic and social development has significantly improved. From 2010 to 2019, China’s gross domestic product (GDP) increased from Chinese yuan (CNY) 41,212 billion (bn) to CNY 98,651 bn. Urban dwellers’ disposable income increased from CNY 19,109 to CNY 42,359 per person, the registered unemployment rate decreased from 4.1 per cent to 3.6 per cent, and industrial and consumption upgrades brought improvement in many regions. However, that prosperity has not been matched in rural areas.

While economic prosperity has propelled some 400 million Chinese into the middle class through strategic development focussed on Tier 1 and 2 cities and China’s coastal regions, that very success has sapped investment and talent out of areas further inland.

This has led to the Matthew Effect (see box)—also seen across the world—in which prosperity grows in advanced urban centres while poverty increases outside them. There is a point at which the ripple effect of economic growth geographically outward from development hubs simply stops. Research has shown that only 22 per cent of suburban counties worldwide have successfully developed dynamic local economies, with the rest either seeing negative growth or declining into commuter belts.

To reverse the trend, government programmes globally have tended to focus on investment in regional technology and manufacturing. This strategy is bound to fail when the necessary highly-educated talent pools or strong manufacturing bases are deficient in the targeted regions.

Case study: Xiuwu County

Xiuwu County in Henan Province has a weak technological and industrial foundation. The added value of its secondary industry in 2015 was only approximately CNY 6.7 billion, ranking bottom in the Zhengzhou metropolitan area. Both the quantity and quality of research institutions and personnel, as well as research and development expenditure, were also significantly lower than the average level within the Zhengzhou metropolitan area and China as a whole.

The challenge for Xiuwu County—and many similar regions both in China and globally—is to focus on its own unique resources to build economic growth: a development path that has been overlooked and does not rely on exceptional technical skills or manufacturing advantages.

The advantages of looking to culture, arts and heritage rather than technology or manufacturing for development are that there are fewer prerequisites for success, as it rests on resources unique to the region. Research has shown that 68 per cent of successful economic development in peri-urban areas was aesthetically driven, while only about 32 per cent could be attributed to technology and manufacturing. There are numerous examples worldwide of successful transformations to an aesthetically-driven economy, including Portland, United States; Rostock, Germany; Kamakura, Japan; and Songyang County in Zhejiang Province.

An aesthetic economy is implemented in three key steps. First, determine ambitious but feasible goals based on a deep analysis of local resources. Second, translate these ambitions into specific projects, such as developing regional crafts or outstanding natural landscape features. Third, ensure that individual projects are connected to each other. This will accelerate progress toward the aesthetic goals set in the first step, including attracting investment, as well as developing stronger local institutions and important infrastructure (transportation or connectivity).

In fact, the aesthetic economy is already having a major impact on large areas of China’s financial base. For example, the market value of home-grown designer brands increased from approximately CNY 28.2 bn in 2015 to CNY 72.1 bn in 2019. The annual income of cultural and creative products of the Forbidden City alone has exceeded CNY 1.5 bn. We are witnessing a new era of innovation in China’s aesthetic economy.

The widening gap between the prosperous centres of China’s rapid industrialisation and their rural hinterlands affects everything from the quality of schools and hospitals to the prospects for Chinese citizens. The traditional route of technology-plus-manufacturing capability-building is often a poor fit and destined to disappoint.

An aesthetic economic strategy offers a new model for many counties in China that do not have strong technology and manufacturing resources to develop and upgrade. For instance, this approach has helped Xiuwu County to leverage its natural, historical and cultural resources to kickstart a new chapter in its development. The number of tourists and level of tourism income have increased about 2.8 times and three times, respectively, over the last decade, driving the local GDP to about 1.7 times that of 10 years ago. This is despite the impact of the pandemic on tourism.

Xiuwu is now an acknowledged leader in the development of both natural and historical heritage, serving as a role model for other counties. The aesthetic economy approach focusses on the unique characteristics of the region rather than forcing compliance with the mainstream. This ensures the unique character of different regions is preserved and nurtured, while also fulfilling development needs. Xiuwu County provides a blueprint for other regions to follow, both in China and in similar regions around the world.

Dereck Ji is EY-Parthenon Partner in the Government & Public Sector at EY-Parthenon Shanghai Advisory Limited. Brian Yu is EY-Parthenon partner in Government & Public Sector at Ernst & Young (China) Advisory Limited.

EY exists to build a better working world, helping to create long-term value for clients, people and society and build trust in the capital markets. Enabled by data and technology, diverse EY teams in over 150 countries provide trust through assurance and help clients grow, transform and operate. Working across assurance, consulting, law, strategy, tax and transactions, EY teams ask better questions to find new answers for the complex issues facing our world today.

This material has been prepared for general informational purposes only and is not intended to be relied upon as accounting, tax, legal or other professional advice. Please refer to your advisors for specific advice.

[1] EY refers to the global organisation, and may refer to one or more, of the member firms of Ernst & Young Global Limited, each of which is a separate legal entity. Ernst & Young Global Limited, a UK company limited by guarantee, does not provide services to clients, nor does it own or control any member firm or act as the headquarters of any member firm. Information about how EY collects and uses personal data and a description of the rights individuals have under data protection legislation are available via ey.com/privacy. EY member firms do not practice law where prohibited by local laws. For more information about our organisation, please visit ey.com.

Recent Comments