China’s circular economy and the growth of energy performance contracting

Energy performance contracting (EPC, also known as energy management contracting) involves an energy service company (ESCO) and an energy consuming entity (ECE) or ‘host’ drawing up a contract detailing the energy-saving goals of a project, such as a pre-existing factory or a building complex. The ESCO provides services such as energy audits, scheme design, funding, operation and maintenance, training and monitoring. The essence of the EPC model is to pay all of the costs of the project out of the ECE’s energy savings. Peter Corne, Yingchu Qian and Vivien Zhu look at how the EPC mechanism is growing in popularity in China, and the challenges ahead for stakeholders.

The EPC model began to emerge in western countries in the 1970s, with projects at that time valued at United States dollars (USD) 6 billion. The US Government has since issued a number of policies and enacted legislation, injecting roughly USD 11 billion worth of incentives into the domestic ESCO market, which may reach USD 15 billion by the end of 2020.

The global ESCO market grew eight per cent in 2017 to reach USD 28.6 billion. China continues to underpin market growth, increasing 11 per cent to USD 16.8 billion in 2017. The US market grew to USD 7.6 billion the same year. In Europe, the market remains somewhat underdeveloped compared to other major regions, representing just 10 per cent of the global total.[1]

In the majority of Asian markets, ESCO activity within the industrial sector represents the largest share, primarily as a result of favourable policy measures and because the energy saving from the industrial component is relatively easy to identify. In North America and Europe, on the other hand, industry plays a more marginal role. This is due to a mismatch between the contract durations on offer from ESCOs and the terms desired by companies, as well as a preference of enterprises to draw upon internal expertise to implement efficiency measures.[2]

The Chinese ESCO market was launched in 1998, with the World Bank providing back-to-back guarantees under a scheme with certain domestic banks. However, the concept took hold very slowly. Back in 2000, annual EPC volume was Chinese yuan (CNY) 1.3 billion (USD 200 million). In 2010, it reached CNY 2.9 billion (USD 450 million). In 2017, business hit CNY 111.3 billion (USD 16.6 billion), and in 2021 it is estimated it will reach almost CNY 205 billion (USD 30.5 billion). Major ESCOs in China include Aliyun, China Southern Power Grid, ENN and Huadian Fuxin Energy. The most successful ESCOs in China are tied to large enterprise groups and hence have ready access to funding.

EPC projects are implemented in both the industrial and the built environments. Examples of the former are using equipment and technology to reduce energy consumption in factories such as steel, municipal gas heating or petrochemical plants; these types of projects normally involve capturing waste products such as gas or heat and reapplying them to the industrial process to reduce energy usage.

In the built environment, EPCs can involve technologies such as solar panels, waste-to-energy, recycling of water, heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC), insulation, and special types of windows, to reduce energy usage and manage ‘comfort levels’. Providing sophisticated EPC solutions is more complicated in the built environment because of the difficulty of determining an energy usage baseline against which savings can be calculated.

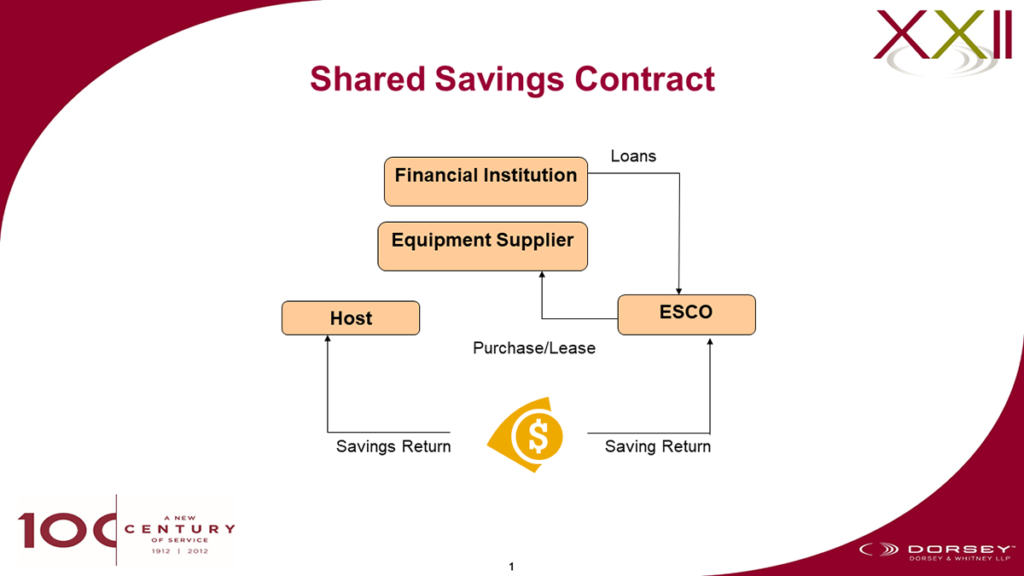

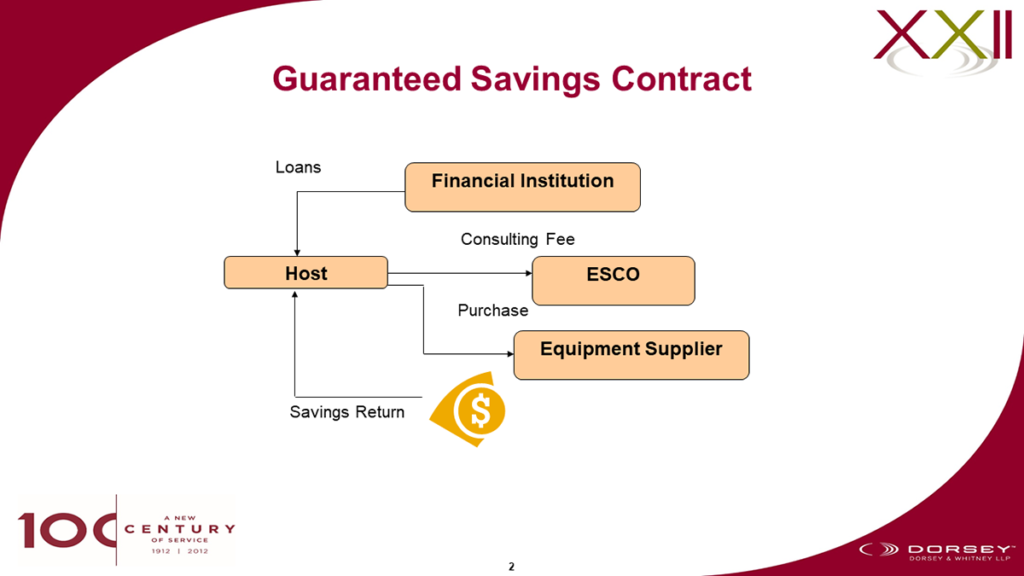

There are two main forms of ESCO energy performance models: the shared savings contract model and the guaranteed contract model. Others less commonly applied are the energy-cost trust contract model and the project finance model.

Shared Savings Contract

Under this model, the ESCO and the ECE share any

profits derived from the energy savings based on a ratio agreed in the

contract. Investment in the project is either made jointly by both sides, or

solely by the ESCO, but either way the ESCO tends to bear most of the financial

risk. Upon completion of the project, ownership of the enabling equipment will

be transferred to the ECE free of charge, and all energy-saving benefits

generated in the future will belong to the ECE. The Chinese Government has supported

the shared savings model vigorously.

Guaranteed Savings Contract

Under the guaranteed savings model, the ECE alone invests in the energy-saving project, while the ESCO provides services and guarantees the benefits. Upon completion of the project and confirmation of the guaranteed saving benefits by both sides, the ECE pays a service fee to the ESCO either in a lump sum or in installments. If the ESCO fails to realise the guaranteed saving benefits, it will bear the shortfall itself. In this respect, the ESCO bears the financial risk in addition to the ECE.

China’s national standards for energy performance contracts

The applicable national standards for energy performance sontracts in China are the General Technical Rules for Energy Performance Contracting (GB/T 24915-2010), issued by the Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine (AQSIQ) and the Standards Administration of China (SAC) on 9th August 2010, effective from 1st January 2011. This standard only recognises the shared savings contract model.

On 25th January 2019, the National Technical Committee on Energy Fundamentals and Management of the Standardisation Administration of China (NTCEFMSAC) published a new national standard draft for comment, in which other models such as guaranteed savings contracts are finally recognised.

The NTCEFMSAC passed the new draft on 14th June 2019, however, it has yet to become effective. Therefore, the 2010 national standard remains in effect even though it is clearly out of date.

National level incentives

For EPC projects that adopt the shared savings model and fall within the 2009 Catalogue of Energy Conservation and Water Conservation Projects, it is possible for ESCOs to apply for tax preferences, such as income tax exemptions from the first to the third year of the project and a 50 per cent reduction of income tax from the fourth to the sixth year.

Local level incentives

At the local level, many of the old financial incentives previously in place have expired. Following the expiration of its incentives for EPC projects in 2015 and 2016, the Shanghai Government published a number of new rules. In 2017, it promulgated Measures on Special Support for Industrial Energy Conservation and EPC Projects, which will remain in effect until 31st December 2021. These measures increased the amount of incentives available while lowering the threshold for qualification. They also, for the first time, include projects under the guaranteed savings model. On 9th November 2019, Shanghai announced a list of 32 EPC projects that would be granted incentives to the amount of almost CNY 152 million. Meanwhile, Jiangsu, Jiangxi, Tianjin, Fujian, Guangdong, Hunan and Chongqing have put in place updated funding programmes for EPC projects that adopt the shared savings contract model.

Barriers in China

The most common problems confronted in the EPC industry in China are the lack of technical capacity, the insufficiency of information, and the lack of monitoring and verification (M&V) standards and tools. Also, a credit system is yet to be put in place that facilitates lending to hosts.

Specifically, under the incentive regimes for EPCs under the shared savings model, the ESCO itself had to undertake the investment in the project, and to incur extra cost and risk. This was exacerbated by the general inability of most privately held ESCOs, due to their small asset base, to provide adequate asset security required by commercial banks for the provision of loans. We have started to see in Shanghai the reorientation of incentives toward project owners with the ability to raise finance and hence invest in EPC projects. It directs incentives toward the investors, which could be either the ESCOs or the project owners.

Conclusion

The prospects for built environment EPCs and the sector’s ability to contribute towards China meeting its energy usage reduction goals should be bright. But while the yet-to-be-implemented new EPC technical standard addresses one of the obstacles by broadening the contractual models acceptable under the incentive regime, the M&V conundrum, its impact on the willingness of banks to extend financing, and lack of support by insurers, are continuing headaches. One option would be to allow foreign companies with a proven track record of technical expertise and experience to operate unified platforms to measure and verify energy savings from a multiplicity of sources, and to set up M&V companies in China with the requisite licences. Such licences have so far been out of reach for foreign enterprises. Further, while some local banks such as Xinye Bank and Bank of Jiangsu have made some progress in this area, more banks should establish specialised energy management project finance divisions to support the financing of EPC projects and the taking of pledges over performance-based project receivables based on energy usage baselines.

China needs a healthy, professionally run and well-financed EPC industry that can penetrate those areas of the economy that drag on its march toward energy efficiency. All circular economies need a robust EPC industry. China should enshrine such a goal within its next five-year plan and put in place all of the components outlined in this article to make the achievement of such a goal a reality.

Contributors’ Note

Peter Corne is head of Dorsey & Whitney’s Shanghai office, co-head of Dorsey’s Cleantech Group, and Shanghai head of the European Chamber’s Environmental Working Group.

Yingchu Qian is General Manager of HARVENCY, Shanghai Distinguished Green Building Expert, Tongji Green Building Mentor, and Senior Advisor for Green Financing for CERC-BEE.

Vivien Zhu is a legal consultant in Dorsey & Whitney’s Shanghai Office.

[1] Energy service companies (ESCOs): At the heart of innovative financing models for efficiency, International Energy Agency, 25th February 2019, viewed 14th January 2020, <https://www.iea.org/articles/energy-service-companies-escos>

[2] Ibid.

Recent Comments