How the private sector can use common prosperity to advance sustainability

At its core, Chinese President Xi Jinping’s common prosperity campaign appears to be about creating a fairer, more equitable society for the entire Chinese population. Since officially declaring the end of extreme poverty in 2021, the Central Chinese Government has doubled down on equalising decades of unequal economic development. A redistribution of wealth, and shoring up a widening income divide, are the key tenets of this ambitious campaign. John Pabon of The Silk Initiative explains how companies can look to common prosperity to advance their own sustainability efforts.

The concept of sustainability has many of the same objectives as President Xi’s common prosperity. To be clear, we’re not just talking about the green side of things – sustainability encompasses so much more. While there are the salient issues of climate change, deforestation and pollution, there are also social issues that fall under the environmental umbrella, such as labour rights, community impact and stakeholder engagement. When we look at sustainability through a private-sector lens, governance issues like transparency, reporting and remuneration take centre stage. No matter which part of sustainability we’re talking about, the ultimate goal is creating a better future for the planet and its inhabitants.

Over the past two decades, one driver of success in sustainability has emerged as more prevalent than any other. The holy grail of evolving the sustainability agenda, especially in China, is for private sector companies to find ways of supporting large government initiatives. The easiest way to explain this is through the eyes of a provincial leader in, say, Anhui Province. They receive targets sent down from Beijing with the tacit understanding that failure is not an option. Yet they aren’t always given the tools to meet these targets. When it comes to environmental or social issues, bureaucrats rarely have the skills to even begin undertaking such programmes.

That’s where the private sector can step in to help. Multinational companies, especially those more evolved in their sustainability thinking, can offer years of experience to help fast-track meeting local targets. In essence, local governments have the drive, ambition and capital. What they lack are the tangible skills to get the job done. The true win-win comes when these worlds collide.

A true win-win

The world of manufacturing can provide a good example. For decades, fast-moving consumer goods companies have used China as their factory, churning out products at rock-bottom prices with an almost endless supply of low-wage labour. When factory conditions in China are mentioned, what do most people in Europe still imagine? Tired workers huddled in cold rooms, at risk of losing a hand if they doze off next to a machine? Dormitories with no air conditioning in the middle of summer, rampant disease and inedible food? Automated machines buzzing quietly while specialised technicians keep things rolling along in near hospital-like conditions?

Wait, what?

The last scenario is certainly different from the sweat factories many outsiders envision, but if people had to guess which is correct, option three would be a wise bet. The level of automation going on in China, and the safe and technologically-advanced conditions in many factories, are astounding. In many automated factories, people are only used to programme instructions into machines. Of course, plenty of things are still done by hand, but these clinical surroundings are hardly the black-market labour conditions many think of. Factories are safe, clean and monitored or audited ad nauseam.

That means big multinational conglomerates could easily just lay off thousands of factory workers and put machines in their place, right? Wrong. Instead, these companies are using this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to instead upskill workers for future employment opportunities. To get a sense of the scale of this undertaking, let’s look at one example of the type of training that can take place.

The basic premise of this particular programme was to help upskill female workers across a company’s China-based factories. The course would cover topics such as on-the-job training, business and management skills, and communications, as well as the soft skills needed to be a good worker: family planning; personal finance; and health and wellness. Over the eight or nine years of compulsory education in China, there is little time to teach things like these.

From a business perspective, what is the rationale for all this? How can a company justify training their workers on such topics, especially when on the surface it seems to be a huge expenditure? Sure, it might make corporate executives feel (and look) good. As with anything related to sustainability and business, though, there has to be an economic imperative for change to happen. In short, how can a business still make money from this programme?

Take the family planning topic, for example. Abortion is still considered a legitimate form of birth control by many in China, and teachers don’t help students to understand the potential complications or alternatives. Touchy cultural taboo subjects such as these are rarely talked about by people, much less by the government. However, when workers get abortions, they are often out sick for several days afterwards. If a worker comes to realise there are other forms of contraception, and in turn gets fewer abortions, then they will show up to work more often. This leads to lower absenteeism, especially when calculated across an entire factory. Not only that, but these women are likely to be happier psychologically and thus less stressed. When someone is happier, they are more productive. Lower absenteeism, higher productivity and the bonus of greater appreciation for the company mean you are going to get more work out of each employee. This means more money for the factory and the company.

A true win-win scenario. But how much of a win-win?

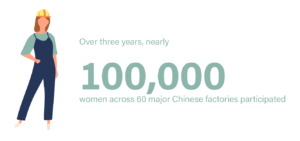

Over three years, nearly 100,000 women across 60 major Chinese factories participated in one programme like this. That’s 100,000 lives changed directly and countless hundreds of thousands more indirectly. The impact on the participants is much greater than that gained from learning just hard skills; more than 70 per cent of employees said the programme helped them adapt better to and solve problems in their personal lives and at work. In addition, a full 80 per cent of factory trainers said their self-confidence and communication skills improved. This is the scale of change the Chinese Government wants, especially through the lens of the common prosperity campaign. That’s the power of the private sector when used as a force for good.

Advancing common prosperity

Most European companies already operating in China are likely to have strong sustainability practices in place. The question becomes how to use them to further government initiatives. Enterprises would do well to keep the following in mind:

- The common prosperity campaign has a particular focus on labour. If your business has a large contingent of workers, ensure basic requirements like social welfare programmes are in place. Re-think all worker programming—both blue- and white-collar—towards addressing key elements of common prosperity. This could include well-being, remuneration or labour rights programmes across the business.

- People cannot be equal if they are not given equal access to resources. Common prosperity is about more than money: having access to clean air, water and food is also critical. For businesses operating in these spaces, or with experience in clean environmental practices, consider how your knowledge can help raise national standards.

- Where are the collaborative opportunities? As a bloc, European companies can collaborate on initiatives based on a shared interest. For example, automotive companies could improve original equipment manufacturer and supply chain performance. Agricultural firms could work on next-generation farming techniques to ensure food security. Consumer goods manufacturers—especially those sharing factories—could create a dialogue around best-practice auditing.

Overall, it is important to remember that the common prosperity campaign poses more opportunities than risks for European businesses. The key is in understanding how to capitalise on these opportunities. Marrying business knowledge around sustainability with the Chinese Government’s social and environmental initiatives is an elegant solution that will allow all to evolve together.

John Pabon is sustainability advisor for Shanghai-based The Silk Initiative and founder of Fulcrum Strategic Advisors, Asia’s only risk management consultancy addressing the intersection of geopolitics, sustainability, and strategic communications. He leads The Conference Board’s Asia Sustainability Leaders Council, is an advisor to the US Green Chamber of Commerce, and author of Sustainability for the Rest of Us: Your No-Bullshit, Five-Point Plan for Saving the Planet.

Recent Comments