Where does the EU stand on China today?

At the last in-person European Union (EU)-China Summit in 2019—although the EU had just labelled China as a partner, competitor and systemic rival—a joint statement was released outlining several areas of cooperation. Since then, there has been a global pandemic; the EU and China have exchanged sanctions; China has experienced a series of domestic crises; and a war has broken out within Europe. With in-person meetings between European and Chinese leaders resuming in 2022 after a two-year hiatus, Ester Cañada Amela, senior business manager for European Affairs at the European Chamber, asks, how does Europe now see its relationship with China?

Ahead of these meetings between EU-China heads, which started with German Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s 4th November visit, an extensive discussion on the EU’s China strategy took place within EU institutions. On 17th October, Josep Borrell, high representative and vice president (HR/VP) of the European Commission, presented a European External Action Service (EEAS) report on the bilateral relationship to member state foreign affairs ministers, and on 20th and 21st October to the European Council. While the EU reaffirmed its commitment to its 2019 approach to China, some important nuances have emerged.

- It’s dependencies, stupid!

The COVID-19 pandemic threatened EU access to critical materials, components and technologies, prompting the European Commission to map out its strategic dependencies;[1] industrial public-private alliances to be established in key areas such as hydrogen, chips and batteries; and the release of a Chips Act aimed at enhancing European semiconductor capabilities, among other actions. Meanwhile, the war in Ukraine highlighted the dangers of over-reliance on an untrustworthy actor like Russia for key inputs, leading to a re-think of the EU’s energy framework as well as plans to reduce dependencies in other areas such as raw materials. Managing dependencies is now a fixture in both EU domestic and foreign policy considerations and it is not likely to go away anytime soon.

2. If the mountain will not come to Muhammad…

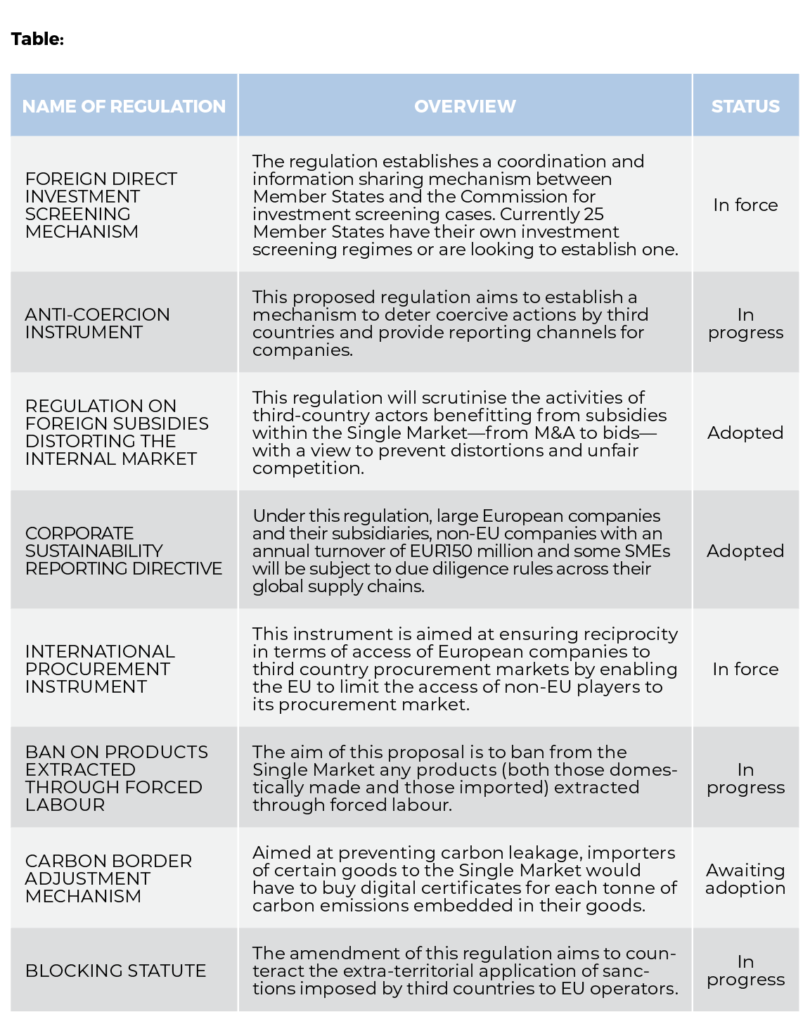

At the tail-end of the Juncker Commission, policymakers became increasingly aware that, rather than waiting for China to change, it was easier to enact changes within the EU itself. This led to a slew of ‘autonomous measures’ – tools to protect the Single Market from distortions caused by third country actors (see table).

3. To be rich in friends is to be poor in nothing

Working with international partners is an important component of the EU’s approach to China. The Juncker Commission oversaw initiatives such as Connectivity Strategy between European and Asia which later became the ‘Global Gateway’ – the EU’s alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative. This trend has intensified with the von der Leyen Commission, with digitalisation, the fight against climate change, defence and promotion of European values increasingly prominent in its foreign, development and trade policies.

One noteworthy bilateral initiative is the EU-United States Trade and Technology Council, which examines areas for potential cooperation like global trade challenges, export controls and foreign direct investment screening.

The von der Leyen Commission has always emphasised expanding the EU’s network of free trade agreements (FTAs) as well as their scope, but the focus on resilience and dependency reduction has added a new dimension to it. For instance, along with proposed legislation like the Raw Materials Act, the EU aims to advance work on agreements with Mexico, New Zealand, India and Chile to increase access to essential materials.

4. The Great Balancing Act

Addressing the European Parliament in late November, HR/VP Borrell posed the following question: “Everyone is fine with us increasing investment in renewable energy and putting up a lot of solar panels. Do you know where they come from? From China. What’s worse then: (not) having them or importing them?”

This illustrates the EU’s double conundrum: although it sees China as a competitor and systemic rival, it is also aware that without China global challenges cannot be resolved. In addition, the deep bilateral trade and investment ties make full-blown decoupling highly undesirable.

On the first front, both the EU and Member States have demonstrated willingness to work with China in areas like global health, food security and most notably climate policy; for example, the 2021 EU-China Common Ground Taxonomy for green project financing.

Positions on the risks and benefits of the bilateral trade links are much more diverse. Members of the European Parliament made it clear that lifting of the Chinese sanctions on European lawmakers is a conditio sine qua non for discussions on adoption of the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) to start, while the Russian invasion of Ukraine has also questioned the effectiveness of ‘Change through Trade’ – a strategy championed by Germany. At the same time, the High-Level Economic and Trade Dialogue in July resulted in, among other things, Chinese concessions on financial services, proving that engagement with the Chinese Government can still result in some gains for European interests

5. United in diversity (of views on China)?

EU Member States, each with their own domestic interests and concerns, are sometimes seen as a target for the Chinese Government to foster disunity within the EU. A prime example is Greece blocking an EU statement at the United Nations in 2017 criticising China’s human rights record. The 16+1 cooperation mechanism between China and Central and Eastern European Countries was once considered a significant source of interference, but is now disintegrating due to ‘promise fatigue’ and increasingly contentious relations between some European participants (such as Lithuania) and China. Moreover, while the recent meetings between German, French, Spanish, Dutch and Italian leaders and President Xi all covered national interests, a number of common threads could stll be found. These include messaging on the war in Ukraine, cooperation on global challenges and, in most cases, mentions of human rights issues in China.

Meanwhile, the European Parliament has become an increasingly powerful actor shaping the EU’s discussion on China. As well as the unity on the Chinese sanctions and the CAI, it was the Parliament that called for the EU ban on forced labour, adopted several resolutions condemning human rights abuses in China and spearheaded outreach efforts to Taiwan.

Public opinion is also a key factor for Member State leaders and EU lawmakers alike, and views on China has steadily deteriorated across the board. According to a Eurobarometer survey conducted in spring 2022, a majority of respondents from 23 out of 27 Member States held negative views of the country.[2]

6. In conclusion…

As

the EU, China and the world have been rocked by events in the past few years,

the EU’s approach to China—while foundationally still based on the pillars of

cooperation, competition and confrontation—has shifted. As a result of COVID-19

and more recently the war in Ukraine, the focus of European policymakers is on

reducing dependencies on what is perceived as unreliable partners (including

China, in the case of rare earths). The realisation that change within the bloc

was easier to enact than change in China also led the EU to roll out defensive

measures to guarantee a level-playing field and reciprocity for European

actors, as well as to address instances of coercion and disinformation

campaigns. At the same time, European leaders recognise the need to work with

China to address global issues, and there is a general acknowledgement of the

strong bilateral trade and investment ties, though assessments on the

risk/benefit balance of these for the EU diverge. Finally, views within the EU

regarding how to approach the relationship with China vary, although recent

exchanges have demonstrated a degree of cohesion on bottom-line issues.

[1] Through two reports rolled out in 2021 and 2022

[2] EP Spring 2022 Survey: Rallying around the European flag – Democracy as anchor point in times of crisis, European Parliament, June 2022, viewed 5th January 2023, <https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2792>

Recent Comments