What businesspeople should know about China’s Five-year Plans

China-watchers will be very familiar with references to five-year plans, which are now in their 14th edition. However, even among such experts, not many know where the plans originated from. Gabor Holch of Campanile Management Consulting outlines how five-year plans developed in China and where their future may lie.

———————

Once a year, the otherwise secretive political system of the People’s Republic of China hosts the ‘Two Sessions’, a forum whose media footprint rivals global award shows. The Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) and the National People’s Congress (NPC) combined exceed five thousand delegates, which includes President Xi Jinping, politicians, local representatives, business tycoons and even faded action movie star Jackie Chan. Twice a decade, this forum is also used to approve the next five-year plan to loud welcome that, like most things coming out of China, echoes what author Luke Patey calls a “dichotomy of overreaction and naiveté”[1] – doomsayers see doom, fans hail a new golden age.

Despite China’s growing worldwide importance, little is known about the creation of its five-year plans. But their far-reaching consequences, and perhaps certain similarities between the Two Sessions and general elections elsewhere, raise expectations well ahead of time. Speculations about the 14th Five-year Plan—once again expected to redraw entire sectors of the economy—started last autumn. Within China, firms cautiously shifted investments to a lower gear in expectation of policy changes, while internet connections wobbled under increased scrutiny. Abroad, multinationals’ headquarters held their breath, mesmerised by the nation at the centre of a global logistical spider web and, this pandemic-torn year, seemingly the world’s only healthy economy.

The regular fanfare around new five-year plans includes elements that can confuse outsiders, from the anachronistic rows of motionless apparatchiks and red flags to propaganda material like ‘The 13 WHAT’, a 2015 music video that attempted to make the 13th Five-year Plan hip.[2] Though its mere quarter-million YouTube views in five years make it a clear flop, the creators of ‘The 13 WHAT’ were right about one thing: five-year plans are “a huge deal – like, China huge!” To appreciate the accuracy of that description, China-based or China-facing business decision-makers should become familiar with the origins and future direction of the plan.

Origins of the plan

The system was originally a blanket adoption from the Soviet Union by China, Eastern European countries and a number of other People’s Republics. Following a 1949 trip to Moscow, Chairman Mao Zedong followed Joseph Stalin’s advice to introduce the plan as an economic blueprint and policy manual for China’s politically inexperienced new leaders. The 1st Five-year Plan (1953–1957) started promisingly. Under the tutelage of thousands of Soviet advisors, in three years China developed several devastated cities into production hubs and doubled the nation’s industrial output. It also introduced legal, agricultural and social regimes befitting a complete economic overhaul.

Sources: www.chineseposters.net

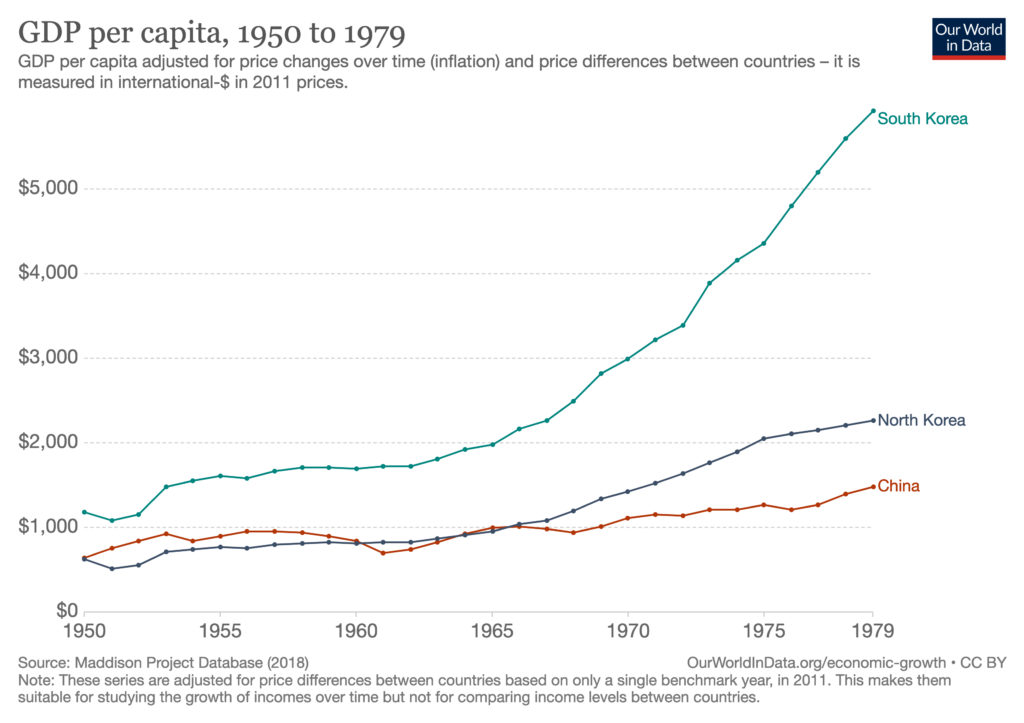

But Beijing’s determination to fix indicators like the urban population or coal and steel production, to reengineer social life, and to pay the Soviet Union in agricultural products for its help, soon backfired with devastating consequences for China’s resources and communities. After Stalin’s death, the two Leninist nations descended into a cold war and the Soviet advisors departed from China. Domestic production fell behind the Party’s soaring targets. By 1957, growth in production and life expectancy had reversed. The next two decades until Mao’s death were overshadowed by the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution. Mired in successive political campaigns, long-term plans were the last thing on anyone’s mind.

Sources: ourworldingdata.org

Deng Xiaoping’s 20 years in charge included his 1992 ‘Southern Tour’, reapproaching the World Trade Organization (WTO) and other milestones of economic liberalisation. But ‘Reform and Opening Up’ never implied abandoning Marxist-Leninist ideology, Party leadership and five-year plans. State officials delegated, as they do today, national targets for indicators that most market economies use to measure rather than manage: gross domestic product (GDP) growth, urbanisation, unemployment and even family sizes. Blanket plans trickle down to specific employment, production and administrative targets for institutions: the armed forces, healthcare, education, and state-owned and private firms. Quotas are set and fulfilled for amounts of coal burned, electricity generated, pills prescribed, babies born, university graduates, new hires at banks, vehicles made, patents registered and fines levied by the police and courts.

Those conducting business with China need to understand the concept of five-year plans due to their pervasive nature. Multinational executives are often surprised to learn that their own firms are also subject to these trickle-down targets. Since the islands of market capitalism in China known as special economic zones attract foreign investment mainly because of the absence of direct state command, foreign firms operating there are controlled indirectly. The state cannot tell global corporations what and how much to produce in China, but it can determine utility and raw material prices, employment quotas (including expats), and ownership and management structures. State-controlled energy, infrastructure, distribution and information technology networks have near-micromanagement power over domestic markets.

Ironically, five-year plans can help well-informed foreign firms thrive in China; they know targets linked to key indicators will be met, come hell or high water. But you don’t need a doctorate in economics to see the futility of planning five years ahead in today’s world. Modern five-year plans still retain essential characteristics of the original Soviet blueprint, which was designed primarily to overhaul heavy industry and the supporting labour force. This is why, well into the 21st century, the plans prioritise GDP growth, infrastructure and urbanisation. Issues like social welfare, science, education and services have played a supporting role, leaving wide gaps that must be filled by local and foreign enterprises.

Foreign firms with ambitions for the Chinese market must ask themselves where their business models fit into the current Plan. Opportunities abound, especially in sectors the state controls but cannot sufficiently supply. This is how the services of global telecommunication firms like Nokia and Alcatel-Lucent get rebranded under state-owned monopolies like China Telecom and China Mobile. Chips by Dutch technology company ASML power China’s electronics industry, and German industrial firms Siemens, Voith and BorgWarner provide the beating heart of power stations, dams and automobiles produced by Chinese firms to realise five-year plans. Similar dynamics make foreign investors upbeat about their future prospects in China’s retail, aviation, medical and professional services industries.[3]

At times it may seem that Beijing is abandoning five-year plans. The absence of an overall GDP growth target in the upcoming 14th Plan has inspired such speculations, but it is likelier that a seven per cent annual goal was deemed too unimpressive to include. China’s five-year plans survived Mao’s upheavals, Deng’s economic reforms and political consolidation, and the technocratic terms of Jiang Zemin and Wen Jiabao. A decade of Xi Jinping’s national revival campaign fortifying national supervision institutions and state-owned firms has further consolidated the role of five-year plans, with the Communist Party at the drawing board. The better the Party’s favourite economic indicators look, the safer the plan’s future. If anything, foreign firms should prepare for closer Party scrutiny in the near future, including the widespread introduction of Party cells in their China branches.[4]

China-based expat executives and their headquarters view five-year plans primarily as a source of stability. China’s market reforms may lag behind WTO schedules, but they unfold safely and steadily. Experienced international project leaders feel prepared to handle associated risks. Toughening import-export and visa requirements can be countered with management localisation and digitalisation. Investment and market strategies can mitigate the impact of sudden policy reversals in fintech, trade and investment regimes or the discreet curbing of Made in China 2025. Meanwhile, China’s emerging walled garden creates a predictably lucrative market for foreign firms. As The Economist Intelligence Unit pointed out, only the Chinese Government has the power to clear entire districts for self-driving cars, to tell companies to produce them and to pressure families to buy them.[5]

Soviet playbook, national roadmap—the two sides of the First Five-year Plan. Source: www.chineseposters.net]

Plans gone wrong—GDP per capita, 1950 to 1979 in China, North Korea and South Korea. Source: https://ourworldindata.org]

The what?—‘The 13 WHAT’ song. Source:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LhLrHCKMqyM]

——————–

Gabor Holch is an intercultural

leadership consultant, coach and speaker working with executives at Asian and

European branches of major multinationals. His Shanghai-based team, Campanile

Management Consulting, has served 100+ clients in 30+ countries

since 2005. An expat since age four, China-based for 18 years and working

globally, Gabor is a Certified Management Consultant (CMC) in English and

Mandarin, certified consultant at the management academies of half a dozen

global corporations and licensed in major assessment tools including DISC,

the Predictive Index and MBTI.

[1] Small and Medium-sized Powers’ Response to China’s Rise: A Conversation with Luke Patey, <https://podcasts.apple.com/hk/podcast/chinapower/id1144663360>

[2] ‘The 13 WHAT’ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LhLrHCKMqyM

[3] European Business in China Business Confidence Survey 2020, p. 8, 14.

[4] ‘The Chinese Communist Party Targets the Private Sector’, Center for Strategic and International Studies https://www.csis.org/analysis/chinese-communist-party-targets-private-sector

[5] ‘The World in 2021’, The Economist Intelligence Unit Asia Perspective,

Share the post "Plan Ahead"

Recent Comments