Europe’s Changing of the Guard and its Impact on EU-China Relations

2019 marks the closure of one chapter in European politics and beginning of a new one. The European elections in May kickstarted an ongoing process that has seen the appointment of the new leadership in key European Union (EU) institutions. In parallel, there has also been a noticeable shift in the EU’s interactions with China throughout the months before the elections, a phenomenon clearly exemplified by documents like the March Joint Declaration and the Joint Statement after the EU-China Summit. In this article, European Chamber Business Manager for EU Affairs Ester Cañada Amela looks into the priorities of the new EU leadership and discusses the role of China in the EU’s strategy.

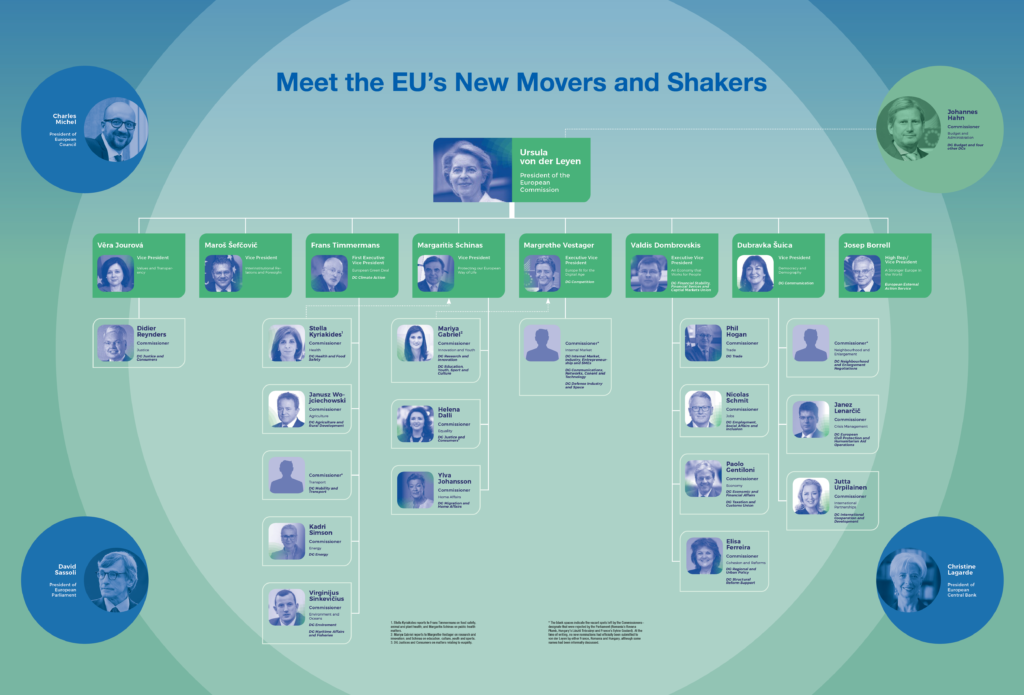

The next constellation of EU leaders

It was a little after 7 p.m. on the evening of 2nd July when European Council President Donald Tusk announced who would be at the helm of the European institutions in the forthcoming years: German Defence Minister Ursula von der Leyen as president of the European Commission, Belgian Prime Minister Charles Michel as president of the European Council, Spanish Minister of Foreign Affairs Josep Borrell as the High Representative for Foreign Affairs, and International Monetary Fund Managing Director Christine Lagarde as head of the European Central Bank. These announcements—the subsequent appointment of David Sassoli as president of the European Parliament went on to complete the picture for the new cohort of European leaders—were the culmination of long negotiations that often went on late into the night by the heads of Member States and their entourage. The resulting nominations embodied a fragile consensus between national leaders, whose inability to agree on a Spitzenkandidat[1] led to the last-minute designation of Ursula von der Leyen and the other nominees as a compromise solution.

Currently the overall structure for the next generation of European leadership is almost finalised. However, there may yet be some changes in the institutional who’s who. Parliament committees and delegations[2] were constituted over the summer, and von der Leyen announced the names of the commissioners-designate and the structure of the new Commission on 9th and 10th September. These initial nominations and structure fulfil von der Leyen’s pledge to achieve both gender equality and geographic balance in the new Commission. At the time of writing,[3] commissioners were undergoing public parliamentary hearings to assess their suitability for the post, with a majority having been recommended for confirmation.[4] However, although the new Commission is expected to be inaugurated on 1st of November, if the Parliament deems some candidates unsuitable —which it has already done, in the case of the French, Romanian and Hungarian nominees— or even rejects the college as a whole, the process could be delayed.[5]

An upgraded strategy for the EU

Upon her appointment in July, von der Leyen presented her political guidelines,[6] which effectively constitute the roadmap for the incoming Commission. Von der Leyen identifies climate, technology and demography as the key challenges faced by the EU, coupled with a changing geopolitical and economic landscape. These and other issues are addressed through six focus areas in her strategy: the much-vaunted, overarching ‘European Green Deal’; a revamped social economic policy; an upgraded push for developing a ‘digital Europe’; a more decisive and cohesive foreign policy; and further efforts to both uphold and advance democratic values in Europe.

The first noteworthy feature of the political guidelines is that they are as much a reflection of the careful balance struck by national leaders as their choices of nominees. This is clearly exemplified in the pre-eminence of the environment and climate-related elements in the strategy, a nod to the European Greens – the fourth most voted for group in the elections. Another key feature is the linkage not only between the main points outlined by von der Leyen, but also between the internal and external dimensions of the new Commission. A clear example of the former is that an area like the European Green Deal has been firmly intertwined with the industrial upgrading of the Internal Market, and is set to play a role in Europe’s foreign policy – especially in trade deals. Digitalisation also permeates areas like the economic upgrade, job creation and the protection of democratic values. Regarding the interaction between the internal and external dimensions, the political guidelines imply that in order for Europe to become a digital and climate leader (as well as a strong geopolitical actor and mainstay of multilateralism), upgrading its market economy to address the new challenges will be essential. This is also reflected in the internal communication structure under von der Leyen. In the new ‘geopolitical Commission’, the College will discuss systematically the external aspects of each commissioner’s work and all services and cabinets will be required to prepare the external aspects of college meetings on a weekly basis.[7]

The China factor

In her opening statement at her confirmation hearing, von der Leyen stressed the need for Europe to find its own path in a world where some countries “are buying their global influence and creating dependencies by investing in ports and roads” and “others are turning towards protectionism” and “authoritarian regimes”.[8] It is clear from this statement that the US and China play an important part in shaping the EU’s overall strategy, if only as mirrors through which to define itself. However, geopolitics is not the only aspect where the US and China are influencing the European strategy. The emphasis on boosting digitalisation and developing a comprehensive industrial strategy with a focus on technological innovation are no doubt at least partly driven by the Sino-American dominance in these areas.

These considerations aside, in order to better understand the China factor in the new Commission’s strategy, one needs to go back a few months in time to look at the outgoing leadership, as the period immediately before the European elections was charged with China-related actions. In March 2019, the Council of the EU adopted a foreign direct investment screening mechanism,[9] and the Commission and the European External Action Service released a Joint Communication on the EU’s relations with China with 10 concrete action points.[10] April 2019 saw the celebration of an EU-China Summit that—through a concerted EU inter-institutional effort towards a stronger and cohesive stance—resulted in a joint statement[11] that tackled key issues for the bloc such as industrial subsidies and forced technology transfers. The statement also established clear timelines for the conclusion of a variety of agreements, including the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI).

All signs indicate that the new leadership will pick up where the outgoing one left off when it comes to its China strategy. To begin with, von der Leyen’s political guidelines emphasise the need for a stronger Europe in the world. That includes developing a free and fair trade agenda, where agreements include sections on sustainable development, environmental and labour protection. A chief trade enforcement officer will monitor the implementation of these agreements, and full use of trade defence instruments and sanctions will be made where necessary. It also includes ensuring that the EU promotes multilateralism and actively participates in the shaping of international institutions such as the World Trade Organisation (WTO).

Von der Leyen’s team seems to be broadly on the same page when it comes to dealing with China. Of particular note was Trade Commissioner-designate Phil Hogan’s China-heavy parliamentary hearing, where he stressed the importance of rebalancing the relationship with China through actions such as developing a procurement instrument, concluding the CAI and strengthening the investment screening mechanism. Hogan also mentioned tackling issues at the WTO level, such as advocating for reforming the body’s ‘developing country’ status and continuing the dialogue with China on e-commerce, as well as in the context of industrial subsidies and forced technology transfers. Hogan was not the only Commissioner-designate to mention China in their strategy: to list just a few, Vice President-elect Margrethe Vestager alluded to it when discussing unfair competition and artificial intelligence; High Representative Josep Borrell when stressing the need for a cohesive voice for the EU in its foreign policy; and Commissioner-designate Mariya Gabriel when talking about preserving the EU’s leading position in science.[12]

Looking

ahead, there are a number of questions that only time and the new European

leadership’s actions will be able to clarify. Some relate to internal issues,

such as how the European Green Deal will be combined with the EU’s industrial

strategy without friction, or finding a balance between encouraging the

creation of European champions without hindering fair competition in the

internal market. Others, like the need to develop a stronger and more unified

European stance in foreign affairs, relate to external aspects of the EU’s

strategy. In any case, it is encouraging to see that the EU is finding a more

decisive and united voice when interacting with Beijing. The fact that the

incoming European leadership is developing an integral strategy that considers

the linkages between the aforementioned two aspects is also a positive sign, as—if

successfully carried out—it will contribute to reinforcing the EU’s weight when

dealing with counterparts like China. In von der Leyen’s words, throughout the

next five years, it will be the EU’s task to “strive for more at home in order

to lead in the world”.

[1] Spitzenkandidaten are lead candidates for the role of Commission president appointed by European political parties, with the presidency then going to the candidate of the political party that can obtain sufficient parliamentary support.

[2] For more information on the Parliament’s committees, please check the following page: <https://www.europarl.europa.eu/committees/en/about-committees.html>

[3] This article was finalised on 11th October 2019.

[4] For more information on the background of the European Parliament hearings of commissioners-designate, please check the following page: <https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/priorities/commission-hearings-2019>

[5] For more information on the current nominees, please check the chart at the beginning of this article. Please note that the composition of the Commission might undergo some changes between the time of the writing and the time of publication.

[6] Von der Leyen, Ursula, A Union that Strives for More – My Agenda for Europe. Political Guidelines for the next European Commission 2019–2024, European Commission, 16th July 2019, viewed 10th October 2019, <https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/political-guidelines-next-commission_en.pdf>

[7] Von der Leyen, Ursula, Mission Letter to the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Policy and Security Policy/Vice-President designate of the European Commission, 10th September 2019, <https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/mission-letter-josep-borrell-2019_en.pdf>

[8] Opening Statement in the European Parliament Plenary Session by Ursula von der Leyen, Candidate for President of the European Commission, European Commission, 16th July 2019, <https://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-19-4230_en.htm>

[9] Council greenlights rules on screening of foreign direct investments, Council of the EU, 5th March 2019, <https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2019/03/05/council-greenlights-rules-on-screening-of-foreign-direct-investments/?utm_source=dsms-auto&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Council+greenlights+rules+on+screening+of+foreign+direct+investments>

[10] Commission reviews relations with China, proposes 10 actions, European Commission, 12th March 2019, <https://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-19-1605_en.htm>

[11] EU-China Joint Statement, 9th April 2019, <https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/39020/euchina-joint-statement-9april2019.pdf>

[12] For more information on the hearings of the Commissioners-designate, please visit the following page: <https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/hearings2019/commission-hearings-2019>

Recent Comments