Trade secrets have become increasingly important for rights holders in China. Davide Follador, Technical Expert at IP KEY describes recent discussions between Chinese and European experts about the state of play and possible reforms plans.

Trade secrets have become increasingly important for rights holders in China. Davide Follador, Technical Expert at IP KEY describes recent discussions between Chinese and European experts about the state of play and possible reforms plans.

Compared to patents and trademarks, trade secrets are relatively new in China’s IP environment, following the adoption of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law (AUCL). in 1993 The Supreme People’s Court (SPC) has attached great importance to the protection of trade secrets, by issuing official interpretations in 2005 and 2006 to clarify important legal points, although the basic provisions for trade secret protection have remained unchanged ever since the adoption of the AUCL, while there have been major revisions to the patent, trademark and copyright laws since then. Chinese legislators have been considering a reform of the AUCL for a few years already and are now moving towards actual amendment of the law. Among IP experts and commentators in China and abroad, there are also those who believe that China should adopt a sui generis Trade Secrets Law, along the same lines that the US is planning on the federal level and the EU might do with the adoption of a harmonisation directive (although in the EU context, the directive should be then implemented into national laws).

Regardless of the approach (either a separate law or chapter in the AUCL), the revision of the AUCL has been included in the legislation agenda of the Standing Committee of the 12th National People’s Congress and protection of trade secrets is expected to be part of this reform.

Regardless of the approach (either a separate law or chapter in the AUCL), the revision of the AUCL has been included in the legislation agenda of the Standing Committee of the 12th National People’s Congress and protection of trade secrets is expected to be part of this reform.

From a policy perspective, having trusted IP enforcement mechanisms in place is crucial for China, as the country aims at increasing the role that innovation plays in its economic development. Sound protection of trade secrets in commercial transactions, employment relations and manufacturing agreements is key to building further trust around China’s overall IP environment, in its goal to become an international innovation hub. Therefore, enforcement of trade secrets cannot be underestimated as a policy priority.

As matters stand, enforcement of trade secrets in China is—like in the EU—a matter of judicial litigation, but in the Chinese legal system trade secrets owners can also rely on a set of administrative enforcement measures aimed at punishing trade secrets violations. The typical administrative enforcement system is led by the State Administration for Industry and Commerce (SAIC) through its provincial and county branches distributed throughout the country.

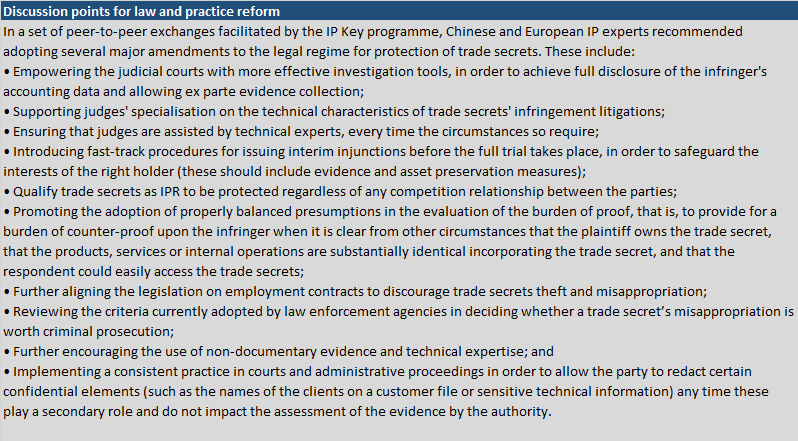

In the last two years, European and Chinese IP experts have been holding exchanges in Beijing through IP Key, the EU-China IP cooperation programme, to identify ways to improve China’s system for protecting trade secrets. Below are some of the key issues and recommendations outlined by experts on how best to improve China’s trade secrets’ enforcement system for the benefit of both domestic and foreign companies.

Enforcement and coordination between administrative and criminal prosecution

China’s current system for trade secrets’ enforcement often struggles when it comes to the application of criminal thresholds, the minimum value needed for a case to become a criminal matter. Assessment of such a value is challenging due to the fact that establishing the profits and losses related to a trade secret’s misappropriation in the early stages is extremely difficult as the rights holder and the enforcement authorities at this time normally lack full information on the extent of the infringement. This has resulted in a relatively low rate of criminal enforcement initiated by right holders so far.

However, further consistency and coordination in the application of the legal criteria for calculating criminal thresholds could be achieved, for example, by encouraging the establishment of permanent inter-agency coordination mechanisms.

Improved coordination should also be achieved in terms of exchange of information and investigative elements, with increased participation of private parties in the investigations, as the IP holders can provide valuable support to law enforcement.

Are value thresholds necessary?

It is noteworthy that financial/value thresholds for criminal trade secret cases are not applied by the vast majority of European countries. There is debate whether there is a rationale for such a requirement at all: in principle, since a theft can be punished irrespective of the value of the stolen object, there is likewise no reason to subject the application of criminal law according to the volumes of profits realised by the infringer or the extent of the losses suffered by the defendant.

The judge or prosecutor could then decide and modulate the severity of the charges and punishment on a case-by-case basis, taking into consideration, for example, the impact on consumers’ safety, the presence of criminal syndicates or other serious circumstances.

The presence of a value-based criminal threshold (刑事门槛) in the current Chinese system was certainly introduced with the purpose of providing legal certainty but has in practice resulted in difficulties of interpretation.

Constitutive elements and legal definition of trade secrets

In most European countries, an infringer can be sued or prosecuted once he or she obtains a secret without the owner’s consent, even if the secret is not directly used to produce similar products.

Courts in the EU also usually make a distinction between trivial knowledge available within a corporation and sensitive commercial or technical information. Judges then consider the various steps that have been taken by the trade secrets owner to preserve confidentiality, such as whether or not a file is specified as ‘private’ or ‘confidential’, access restrictions are in place, the existence of confidentiality agreements have been entered into with employees or third parties, or data encryption has been applied. Once this is established, the burden of proof on whether or not the alleged infringer actually knew that the information was secret can be shifted on to the defendant, if he or she objectively should have known. This obviously requires a balanced assessment of interests and positions.

In China, there have been some positive developments in this regard, looking at the recent judgements selected by the SPC as guiding cases in 2014, which gave clues on how to decide the bad faith of the infringing company as well as whether the acts of the former employee constitute the infringement of trade secrets.

Evidence collection and burden of proof

Evidence collection in China is often problematic due to several factors, such as the absence of discovery procedures and the preference normally given to documentary evidence over witness testimony or technical experts.

Also, as the infringer has absolutely no interest in cooperating with the claimant, it is extremely difficult to collect and submit evidence of misappropriation or violation of trade secrets. In addition, the evidence collection system remains largely dependent on the ex officio investigative powers of the administration/court, which can issue orders to the infringer to exhibit documentation and evidence. However, in practice, evidence gathering remains largely ineffective due to the relatively low fines applicable in cases of non-voluntary compliance.

As to the burden of proof, it may be very useful to further implement pre-trial evidence preservation procedures in the Chinese court system as well as to support ex parte investigations. To date, this has been limited in the practice, particularly in comparison with other forms of IP.

Chinese courts place a heavy burden on the plaintiff to provide direct evidence of a trade secret’s theft. However, claimants usually don’t have the means of proof, apart from initial/circumstantial evidence or reasonable assumptions.

With respect to this, the SPC clarified that ‘secrecy’ could be established in the presence of preponderant evidence of confidentiality measures put in place, and if the applicant reasonably explains how the trade secret differs from public domain knowledge.

Looking at the Chinese legal framework, it would also be important to reach clear standards of proof regarding indirect unauthorised usage of a trade secret.

The SPC specified in past judicial opinions and interpretations that a presumption of unfair acquisition of trade secrets could apply if the right holder provides evidence that: 1) the trade secret is identical or quite identical to the information possessed by the defendant; 2) the latter was actually in a position to access such information; and 3) there is substantial evidence that the defendant has acquired the information by unfair means.

Chinese courts usually apportion a relatively low evidentiary value to court experts’ opinions, when in fact they could be crucial in proving that a defendant’s products incorporate a trade secret and that it was acquired illegitimately. It is quite significant that the newly established IP Courts have already introduced new practices that include larger use of technical expertise reports.

Preliminary and interim injunctions

Preliminary injunctions play a key role in limiting the adverse consequences of a trade secret’s misappropriation. When ordered in due time, they represent the only way to limit the prejudice suffered by the claimant. However, in contrast to the Chinese Patent Law, Trademark Law or Copyright Law, the use of preliminary injunctions in trade secret cases has been rather limited in China, with one of the first preliminary injunction ordered in August 2013 in Eli Lilly v Huang, following the amendment of the Civil Procedure Law in 2012.

Provisions in force in many EU Member States ensure that the competent judicial authorities may, at the request of the trade secret holder, order interim measures against the alleged infringer to impose the cessation of the use or disclosure of the trade secret on an interim basis, as well as bans on producing, offering, placing on the market or using infringing goods, inclusive of seizure and prohibition to import, export or store infringing goods for such purposes.

In the current Chinese system, it is still difficult to obtain the seizure of manufacturing machines and devices, while obtaining the seizure of defendant’s assets for damage recovery purposes can be challenging or subject to high monetary bonds.

These measures aim at providing rights holders effective tools to contain the adverse consequences of an alleged infringement in urgent cases, and according to the experts these instruments should therefore be further promoted in the Chinese court enforcement system.

Confidentiality in enforcement proceedings

Maintaining confidentiality in enforcement proceedings is essential to prevent further violations, but this must be balanced with parties’ rights to access hearings or evidence.

Experts recommended implementing a consistent practice in court and administrative proceedings allowing a party to black out certain confidential elements (such as the names of customers or sensitive technical information) when they play a secondary role and do not impact the assessment of evidence.

In addition, it is important to restrict access to hearings to the parties and their legal/technical counsels, and to ensure the confidentiality of external technical expertise through non-disclosure agreements.

In some EU jurisdictions, such as Italy, trade secrets belong to the category of IPR, therefore damages in trade secret litigation cases are assessed according to the same criteria applied to other IP cases. A trade secret right holder may be awarded an amount corresponding to either the infringer’s profits or the rights holder’s losses, whichever is greater.

In order to calculate losses, the first question is how much more the right holder would have earned compared to the actual revenues in the years of reference if it had been marketing its goods or services without being subject to the theft of its trade secret.

Likewise, assessing the profits realised by the infringer requires consideration of the greater revenue earned, as the infringer didn’t have to bear the R&D and marketing expenses.

Other elements to consider in the assessment of damages should include image or reputational damage, prejudice to goodwill, advertising investments made over the years and legal fees, among others.

Exchanges held in Beijing, Shenzhen and Guangzhou showed that Chinese courts apply the same general principles for calculating damages as in the EU, although in practice a number of difficulties and inconsistencies in the assessment of damages still remain. This situation is definitely expected to improve with China’s newly established IP Courts, which are hopefully going to function also as case-law harmonisers under the guidance of the SPC.

In the judicial practice of many EU Member States, competent judicial authorities may order that information on the origin and distribution networks of the infringing goods or services be provided by the infringer and any other person involved in the distribution of infringing goods.

Since infringers’ account books are seldom available, or reliable, it is challenging to accurately assess the profits and losses. Statutory damages are therefore the last resort for trade secret holders.

A trade secret owner may seek statutory damages according to Article 20 of the AUCL but the large majority of trade secret holders consider the amount of damages awarded by courts to be still insufficient as compensation for the stolen trade secret, which is often of great economic value.

Both EU and Chinese experts agreed that the damages from trade secrets violations do not only originate from direct losses or profits, and that the competitive advantage of holding and exploiting a trade secret should be also taken into consideration. Also, while the administrative authorities are unable to award damages, if this power was granted to the SAIC/AIC, this could act as an additional deterrent to potential infringers. On the other side, though, more effective civil and criminal trade secret enforcement remedies by specialised IP Courts should be adopted, as trade secrets protection is complex and often requires highly technical expertise.

Employment relations and violation of trade secrets by non-competitors

While theft of trade secrets by former employees is a quite common pattern in most trade secret infringement cases around the world, right holders in China face several difficulties in enforcement actions, mainly due to a heavy burden of proof.

The Chinese Labour Law provides that the parties involved in an employment contract may reach an agreement “on matters concerning the commercial secrets of the employing unit”. Employees who are in violation of the conditions specified in the law or violate terms on confidentiality agreed upon in employment contracts—and thus have caused economic losses to the employing unit—shall be liable for compensation in accordance with the law.

One of the expert proposals is to establish by law that, in force of an employment contract, an employee is bound to keep confidential any information obtained during the employment period. The non-disclosure obligation should remain valid after the employment period terminates.

This might be achieved by upgrading trade secrets to a full category of IP on the same level of patents and trademarks, where infringement is punished regardless of competition relations. In the Italian Civil Code, for example, any breach of a non-disclosure agreement leads to contractual liability together with extra-contractual liability since trade secrets are a form of IP like a patent.

In China, protection of trade secrets is limited to competitors. Under the AUCL, only action against competitors is allowed, not against non-competitors.

During the workshops organised by IP Key it was suggested that the future amendment of the AUCL include a provision that trade secrets can also be enforced against non-competitors, in particular against former employees, partners and shareholders.

Current workings of revision to the trade secrets and Anti-Unfair Competition Law

The State Council Legislative Affairs Office has listed the reform of the AUCL, which includes provisions on protection of trade secrets, as one of its priorities for preparatory work and submission to the National People’s Congress (NPC) in the near future. Revision of the AUCL has been included in the legislative agenda of the Standing Committee of the 12th NPC (and upcoming 13th), while the SAIC is working on a draft revision of the AUCL. Furthermore, provisions on judicial litigation over trade secrets’ violations might be incorporated into a revised Civil Code in the future.

In recent years, many new issues and challenges have emerged in anti-unfair competition which also affect trade secret protection. As China is making efforts to build an innovation-driven nation, it is necessary to amend the legislation on trade secrets, either in the framework of the current AUCL or through a separate law, for the purposes of encouraging fair competition, preventing anti-competitive behaviour, as well as protecting lawful rights and interests trade secrets holders and consumers alike.

© 2015, Davide Follador. Follador is a long-term expert at IP Key in Beijing. The IP Key project is the European Commission’s financial vehicle for the EU-China New Intellectual Property Cooperation, an agreement between the EU and China. The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the writer and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union or IP Key

Acknowlegdements and credits

The writer would like to thank in particular professor Christoph Ann (Technische Universität München), Justice Edger Brinkman (The Hague IP Court), Justice Angel Galgo Peco (Madrid Commercial Court), professor Cesare Galli (University of Parma), professor Jean Lapusterle (CEIPI Strasbourg), Dr Qu Xiaoyang (QBPC – Siemens IP Division), the officials and experts of the State Administration for Industry and Commerce of China, as well as the Law School of South China University of Technology in Guangzhou, for their valuable contributions and cooperation during the above described exchanges in China under the IP Key programme.

Recent Comments