Globalisation has not just created immense value for China, as it has for Europe, it has also given the country the ability to exert significant influence over global supply chains, which are now heavily reliant on exports from China. While it should follow that China would do everything in its power to protect the system that it has benefitted from, its security-orientated and self-reliance-focussed policy direction is instead contributing to a more strained global trading environment. China’s willingness to use its dominance in supply chains to exert pressure on its trade partners, for example through export controls, is being met by increasing pushback from other countries and regions. This may result in a reduction of both China’s influence over supply chains and the benefits of global trade, as trading partners take necessary steps to reduce dependencies on China.

China is currently the world’s only manufacturing superpower, with the efficiency and competitiveness of its supply chains making it an exceptionally attractive base for manufacturing and sourcing for many companies. However, long-standing pain points of operating in China—like discrimination in procurement and broadly applied industrial policy, as well as new challenges like tariffs and export controls—are compounding the challenges of a global business environment that is increasingly politicised, uncertain and susceptible to disruptions. The result: companies are struggling to balance the positive aspects of Chinese supply chains against the need to ensure flexibility and resilience.

There are external factors at play that China cannot directly control—such as the United States’ (US’) shift away from globalisation through its ‘America-first’ approach—but it could be more cognisant of how its actions ultimately influence the decisions that other markets may take in response. Many of the concerns that the US has expressed about how China has been able to use its manufacturing prowess to dominate global trade are widely shared by other markets, including the EU. While the EU has been slow to react to this, China’s 2025 imposition of export controls on rare earth elements (REEs) and its subsequent announcement of extraterritorial controls may have been a turning point, with Brussels now seriously considering how to reduce its dependence on China for critical materials.

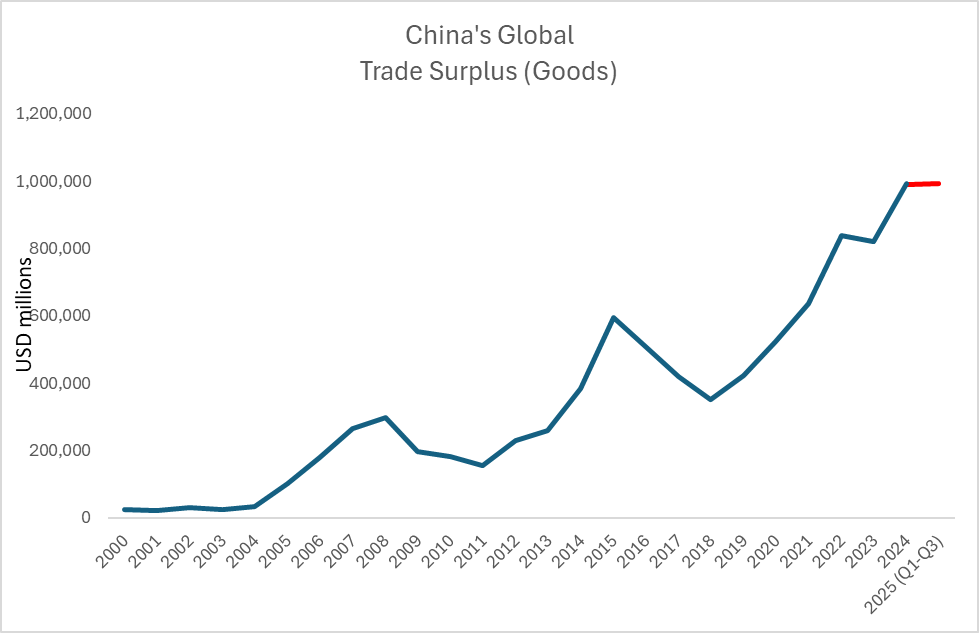

Given that the EU is still in the early stages of its response, it is not possible to predict how its overall approach to China, and trade in general, will evolve. With limited exception, it has both adhered to and defended WTO principles, welcomed most Chinese investment into its Single Market and used carefully targeted, measured trade defence actions only when clear market distortions have been identified. China has benefitted from this approach so far, allowing it to address tensions with the US through disruptive retaliation while knowing it could count on the EU as a stable, albeit discontented, trade partner. However, by continuing to export ever greater quantities of goods to the EU—in part to compensate for weak domestic demand relative to supply growth—while failing to address several long-standing concerns that European companies have about the country’s business environment, China is pushing the EU to take a more offensive approach to its China policy than it currently does.

For now, however, China’s exports to the EU are continuing to grow at a rapid clip. This is perhaps providing a false sense of security that its current policy focus on security and self-reliance—while it reaps the benefits of its dominant position in global trade—is both correct and sustainable. But while the strength of China’s industrial clusters mean that many global companies are still heavily reliant on the country’s supply chains in order to remain competitive, the way geopolitical events—like the US-China trade war—have directly impacted companies has made clear the danger of single-country dependencies, especially on China. This is further accelerating the shift in the way companies view their supply chain strategies, as they increasingly prioritise resilience and flexibility over cost and efficiency.

Over time, China’s ability to exercise control over key supply chains through measures like tariffs and export controls may diminish as other countries’ self-reliance initiatives mature. Most European companies present in China today will remain for as long as they can, given that the country’s innovation ecosystem and unparalleled manufacturing capacity will remain strengths. But both their willingness and ability to place China at the centre of their global supply chains may well diminish depending on if and how China decides to continue leveraging its current dominance.

Source: General Administration of Customs

Note: Dealing with Supply Chain Dependencies: Challenges and Choices was published by the European Chamber on 10th December 2025. You can read the full report by scanning the QR code or visiting: www.europeachamber.com.cn

Recent Comments