An examination of e-commerce disruption

It is known as the ‘Amazon effect’ or ‘Ali effect’ – the disruption that happens when e-commerce behemoths enter a new corner of the retail market. This new commercial marketspace is an internet-based model with online services integrated into offline experiences and logistics by utilising new technologies, such as big data and artificial intelligence. In this article, Rob Wilson, Manny Picciola and Maria Steingoltz, managing directors in L.E.K. Consulting’s Food and Beverage practice, along with Cherry Li from L.E.K. Consulting (Shanghai), outline these new e-commerce trends in the grocery landscape and what the implications may be for both the United States (US) and China.

On 16th June 2017, Amazon announced its United States dollar (USD) 13.7 billion acquisition of Whole Foods Market, a grocer with more than 460 brick-and-mortar stores in the US. In November 2017, a similar situation arose in China, with Alibaba’s (Ali) USD 2.9 billion investment in Gaoxin hypermarket. Both deals sent shock waves through traditional retail sectors that were already struggling with razor-thin margins and cutthroat competition.

In both the US and China, e-commerce penetration of the food and beverage sector has been small in comparison with other sectors, such as electronics and clothing. As of 2017, the food and beverage retail sector only claimed approximately two per cent of online sales in the US, while in China it reached three per cent in 2016.[1] Internet sales will increase globally, with China developing quickly due to its advanced mobile technologies, rising social media influence and changing consumer habits. Even with China’s rapid pace of development, the experience of Amazon, a long-standing e-commerce company, is still worth noting for its impact on the grocery landscape and for its promotion of online-offline synergy.

The online land grab

Traditional grocery stores

Competition among grocery retailers had been escalating well before Whole Foods joined the Amazon portfolio. For decades, a typical store’s net profit had hovered in the low single digits. Now, traditional grocery stores are feeling the pressure of ‘food being everywhere’ as other retailers (e.g. discounters and convenience stores) also turn to fresh and processed foods as a way to drive traffic in their stores.

Against this backdrop, grocery investors did not take kindly to the news of Amazon’s acquisition of Whole Foods. While Amazon’s own stock price stayed about the same, the stock prices of five other US retailers—Walmart, Costco, Sprouts, SuperValu and Kroger—fell an average of 15 per cent over the next two days.

With Whole Foods, Amazon gained hundreds of potential distribution hubs, as almost all US households, 33 million, are within five miles (mi) (approximately eight kilometres [km]) of a store. Among households with income over USD 100,000 per year, 33 per cent are within 3 mi (approximately 5 km) of a Whole Foods. Interestingly enough, food traffic at Whole Foods increased 33 per cent in the week after the acquisition.[2]

Online-offline integration

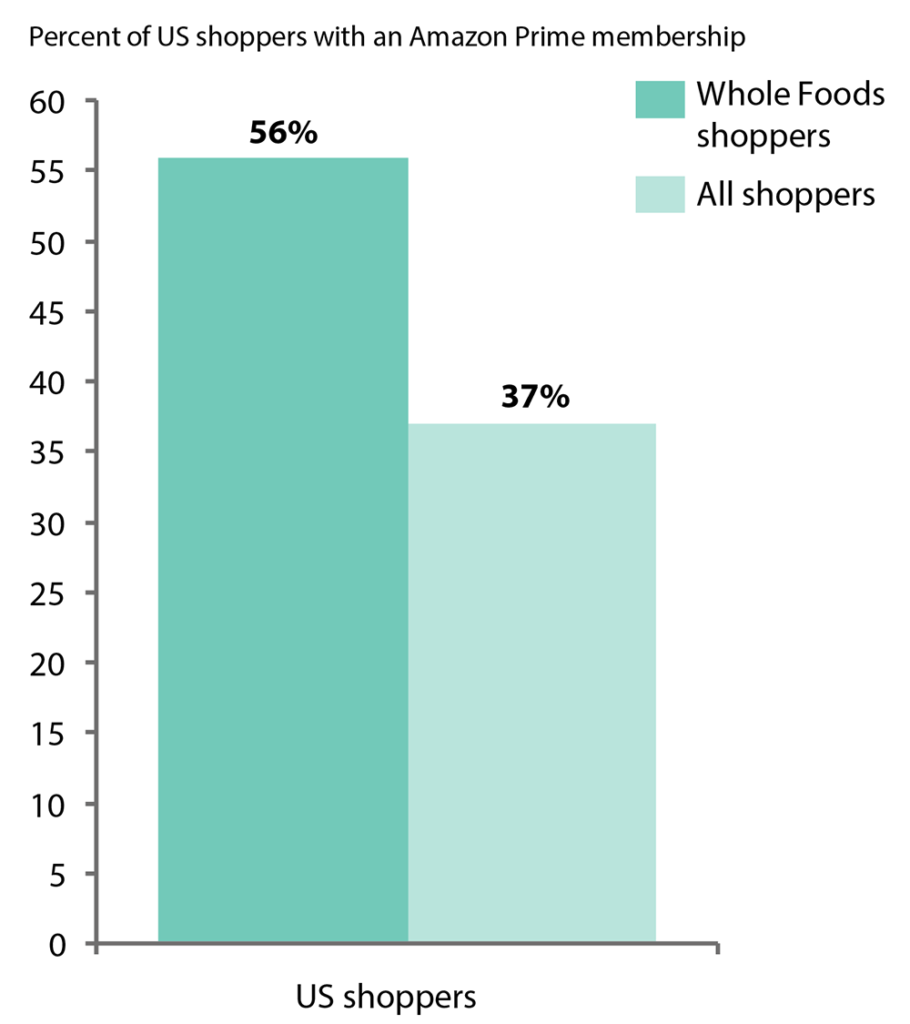

Amazon’s next move was to integrate Whole Foods with its ‘Prime’ subscription service. Taking advantage of a strong overlap between the two sets of customers (see Figure 1), the company began offering to Prime members the ability to order pantry items online from the Whole Foods 365 house brand. Later, Amazon announced the rollout of ‘Prime Now one- and two-hour grocery order delivery’, plus an extension of its five per cent cash-back deal for Amazon Prime cardholders that make purchases at Whole Foods. As it increased the visibility of Whole Foods online, Amazon likewise raised its own profile at Whole Foods nationwide.

This is not uncommon in China. In 2017, Alibaba bought an 18 per cent stake in Lianhua Supermarket, a chain under the Bailian Group, which has 4,800 stores. In the following years, Ali plans to connect their online and offline platforms by aligning product prices, promotional activities and their supply chains to create one unified product. In addition, consumers may also have additional discounts if they pay with Alipay at a Lianhua Supermarket – similar to what Amazon is doing in the US.

Up-and-coming business models

The integration of Whole Foods with Amazon Prime raised speculation that newer, more efficient grocery players would start emulating Amazon’s model. This has escalated an already-pitched battle for control over the ‘last mile’ of grocery distribution. Brick-and-mortar grocers, for example, are experimenting with store pickup of online orders. For example, in 2016, Kroger added more than 420 kerbside pickup locations, now totalling 640.

The Chinese brick-and-mortar grocers are also actively trying new approaches. For example, Yonghui Hypermarket launched the Yonghui Life Initiative in 2015, which included the establishment of Yonghui Life convenience stores and the creation of an application (app). As of 2017, there were 172 Yonghui Life convenience stores across the country, each having approximately 800 stock keeping units (SKUs) of fresh food. Consumers can shop in-store or on an app and have their orders delivered to their homes in 30 minutes, within a distance of 3 km from the store.

On the delivery side, grocery stores are pairing with fleet services at a brisk rate, including Kroger and Uber, Walmart and Instacart, and Aldi and Instacart. Grocers are also eyeing meal-kit companies like Plated. In China, their counterparts are also integrating fleet and food services, with Didi incorporating food delivery services into their repertoire and Meituan stepping into ride-hailing.

Evolving shopping behaviour

Penetration of online grocery

That new generation—tech-savvy, experience-oriented and pressed for time—make up the future of digital groceries. By 2025, millennials will comprise 75 per cent of the US workforce, with most being willing to shop for groceries in whatever format best suits their lifestyle.

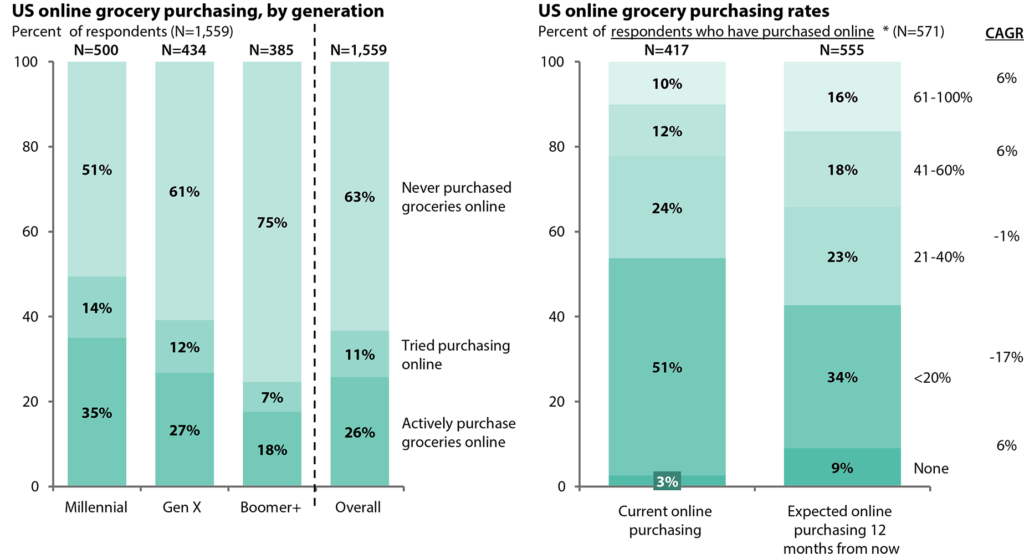

That could be any combination of online delivery, in-store pickup, automatic subscription or virtual supermarket. Today, roughly 40 per cent of consumers have used online or e-commerce grocery services (see Figure 2).

Personalisation and convenience

As e-commerce retailers continue to ease the path to making purchases and online grocery shopping continues to improve, consumers will gain a personalised, curated shopping experience via loyalty rewards, one-click purchasing capabilities and preset delivery specifications. This approach helps consumers shop more efficiently, leading to less browsing by repeat shoppers.

Crowdsourced dynamic shelf

A key advantage to using digital shelves is that they let consumers provide real-time feedback to retailers and manufacturers by rating and reviewing products, responding to questionnaires, and posting photos. Online reviews deserve their own mention, because shoppers often rely on these to make their purchasing decisions and are more likely to buy something new if the product has already been reviewed.

The imperative to adapt

Amazon’s online shopping site, along with its Echo and Alexa products, use proprietary data capturing and analytical tools. These tools track each consumer’s online activity, so Amazon can show advertisements, inventory and store layouts that more closely match the consumer’s preferences. These tools also optimise distribution logistics for both the supplier and consumer. Following this trend, Ali and JD.com are installed with similar tools to achieve the same end goal.

This has several implications for grocers. One, is that with the tools Amazon, Ali or JD uses they can create trend-forward, private-labelled products to feature on a digital shelf. Another is that digital grocers can offer wider brand and product assortments than their brick-and-mortar counterparts who are cost-sensitive to the physical spacing issues that come with shelving and inventory.

Meanwhile, fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) manufacturers can study Amazon’s efforts with Whole Foods to see what they can apply to their own digital grocery endeavours. At a minimum, firms will need to do the following:

- Develop a comprehensive digital strategy – FMCG companies will need to strike a balance between what they require from their own website and what they require from an ‘e-tail’ partner model.

- Optimise the digital shelf – Free from the constraints of physical space, firms must develop capabilities for managing their digital assets and showcasing their products for consumers. They also need to manage online reviews and feedback.

- Rethink price pack architecture – Digital groceries offer the chance to create ‘swim lanes’ for different product configurations that are attuned to the needs of online shoppers and that mask product price comparisons with traditional channels.

- Package for at-home delivery – Collaboration with leading suppliers is required to develop distinctive, efficient direct-to-consumer packaging. This includes rethinking external packaging, boxes, pouches and envelopes.

Much has changed since e-commerce companies’ initial foray into the grocery market. With these changes in technology and e-commerce companies’ willingness to embrace brick-and-mortar retail, the message for food retail becomes clear: in store or online, the world of groceries is going digital, and it is time for brands to get on board.

L.E.K. Consulting is a global management consulting firm that uses deep industry expertise and rigorous analysis to help business leaders achieve practical results with real impact. Founded 35 years ago, L.E.K. employs more than 1,200 professionals around the world. L.E.K. entered China in 1998 and has since become a leading commercial adviser.

[1] https://www.kantarworldpanel.com/cn

[2] Data from research firm, Thasos Group

Recent Comments