What you need to know

Due to the looming climate crisis, governments around the world have taken actions to encourage greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reduction. However, the rate at which steps are being taken varies across economies. In order to protect European companies that comply with strict European Union (EU) carbon neutrality measures, the bloc has introduced a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). In this article, Wei Lin, Richard Lin and Nat Lin of KPMG China provide an overview of how the mechanism will affect companies exporting from China to the EU.

Launched in 2005, the EU’s Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) has been the cornerstone of the bloc’s policy on addressing climate change. Operating under a ‘cap and trade’ scheme, the EU ETS sets a cap on emissions for obligated emitters each year, who are required to purchase and remit emission allowances.

Since then, GHG emissions in the main sectors covered—which includes power and heat generation, as well as energy-intensive industries—have dropped by 42 per cent.

In its Green Deal, approved in 2020, the EU announced its ambitious target to halve net emissions by 2030 compared to 1990 levels, and for Europe to become the first climate-neutral continent by 2050. In 2021, as part of the Green Deal, the European Commission adopted a package of legislative proposals called ‘Fit for 55’, to facilitate the necessary acceleration of GHG emissions reduction in the next decade.

However, while the EU is successfully reducing GHG emissions, many other countries have not yet made reductions or are increasing emissions. The EU hopes to exert global influence on combatting climate change with its Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), an essential part of the Fit for 55 package. The CBAM is aimed at preventing ‘carbon leakage’ by imposing an emissions-based levy on imports of certain products, thereby maintaining the competitiveness of EU production in carbon-intensive sectors.

Scope and timeline

The European Commission’s proposed CBAM focusses on five sectors, referred to as the ‘Covered Sectors’: iron and steel; aluminium; cement; chemical fertilisers; and electricity. It is expected to come into force from 1st January 2023, with a three-year transitional period until 31st December 2025.

On 15th March 2022, the European Council reached consensus on the CBAM and started negotiations with the European Parliament, including on expanding the scope to cover further carbon-intensive sectors such as chemicals and shortening the transition period to two years. Once implemented, the CBAM will gradually expand its coverage to other products that fall within the scope of the EU ETS.

CBAM requirements

Obligations under the CBAM are threefold:

- Companies need to declare carbon emissions embedded in the imported products. Though the importer in the EU is responsible for making the declarations, the manufacturer must provide the carbon emissions data of the imported products. Manufacturers that do not provide adequate carbon data may encounter ‘push-back’ from EU buyers and subsequently lose market share in the EU.

- An independent and accredited verifier must verify the embedded emission quantity. This is one of the key ways the CBAM differs from ordinary taxes. Companies must ensure that the declared emissions embedded in the imported goods be verified by an independent and accredited verifier. Otherwise, emissions subject to ‘taxes’ will be determined using default and unfavourable values for that type of good, such as the average emission intensity of the top 10 per cent worst-performing EU entities.

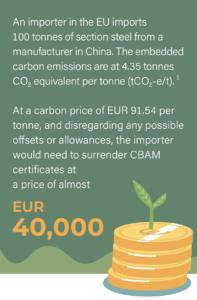

- Companies need to purchase and surrender CBAM certificates according to these emissions (after the transitional period). The CBAM certificate is priced according to the weekly average auction price of the EU ETS allowances. For indicative purposes, the EU Allowances (EU ETS) Futures Price on 6th May 2022 was euro (EUR) 91.54 per tonne.

Potential impacts in China and across the globe

The following example illustrates the potential carbon ‘tax’ impact:

A key question is who will absorb the cost: the importer, the manufacturer or both? While the market will ultimately tell, it seems likely that consumers will bear the brunt of the costs.

On the bright side, the ETS and the CBAM are tax systems for which ‘taxpayers’ are encouraged to take proactive actions to mitigate their tax burden. With the ETS and the CBAM in place, the value of a low-carbon product or project would extend beyond branding and risk management. It would also mean price advantages and a bigger market share; tradeable assets and potential trading gains in secondary markets; and lower financing costs and higher market value in capital markets.

If we take as another example a scenario outlined by the World Steel Association of imports of low-carbon section steel with carbon emission intensity at 0.762 tCO2-e/t,[2] the carbon tax would be around EUR 7,000, less than one fifth of the ‘original’ high carbon intensity product.

Considering that the volume of steel exported from China to the EU and the United Kingdom hit just under 3.2 million tonnes in 2021,[3] a carbon tax could have a heavy impact on companies’ profit margins unless actions are taken.

Not just about money

Ensuring emissions and reductions are measurable, traceable and accurate—i.e., a reliable monitoring, reporting and verification system—will be the cornerstone of carbon management systems. Whilst most businesses in the EU already have a certain level of GHG management systems in place, many companies in China do not yet have even a minimum set-up. For businesses operating in the Covered Sectors as well as the supply chains of the Covered Sectors, it is critical to improve management’s environmental awareness as well as to understand and enhance corporate CBAM readiness. A good starting point would be to conduct an initial GHG management baseline assessment, including a product-level GHG emissions quantification exercise for CBAM purposes.

Vendor engagement, rather than vendor management

In relation to supply chains, businesses normally use the term ‘vendor management’. However, when it comes to environmental management, the term ‘vendor engagement’ seems more appropriate. With the CBAM, vendors and customers will need to cooperate and help each other.

Vendor engagement for the CBAM will entail a lot of work ─ including checking data quality against CBAM compliance requirements; getting the GHG data and management verified; as well as juggling timelines and multifaceted coordination among internal and external stakeholders.

Digital applications such as software-as-a-service or blockchain solutions can enable automated processes, big data analytics and dashboarding, and transparency across the globe, making vendor engagement programmes easier and more reliable. These systems are flexible enough to meet individual organisations’ business needs, and are becoming increasingly affordable. Another option is to outsource vendor engagement to agents, even if just on a temporary basis.

Summary

There are many things to consider when commencing CBAM and other GHG management work, and it is a complex process. This article has identified some key points to take into account when starting this process. The aim is for this article to also inspire companies to take action in preparing for the CBAM, which will be an important step in moving towards more sustainable supply chains and a greener world.

NOTE: This article was written in May 2022. On 8th June 2022, the draft legislation on the EU CBAM was referred back to committee by the European Parliament. It is believed that the Committee on Environment, Public Health and Food safety will revisit the CBAM legislation for the parliament’s first reading in the near future.

KPMG China has developed a

leading practice in the field of GHG Emissions and Reduction. Most importantly,

we do not see ourselves as mere consultants. KPMG professionals want to work

collaboratively with clients on the journey to a low carbon future. Wei Lin is

partner and head of KPMG China’s Strategy & Operations practice and the

Environment, Social & Governance (ESG) practice. He is a member of KPMG

China’s Board of Directors, as well as KPMG Global ESG Steering Committee. Richard

Lin is partner of KPMG China’s Supply Chain Practice, responsible for GHG

emissions and reduction related services. Nat Lin is associate director of KPMG

China’s Supply Chain Practice.

[1] Source: China Products Carbon Footprint Factors Database 2022

[2] Source: <https://www.galvanizing.org.uk/sustainable-construction/steel-is-sustainable/steel-embodied-carbon/>. Please note that this carbon emission intensity is for indicative purpose only.

[3] Source: China Iron and Steel Association; <http://www.chinaisa.org.cn/>; please note that the EU CBAM does not apply to the United Kingdom.

Recent Comments